1. Abstract

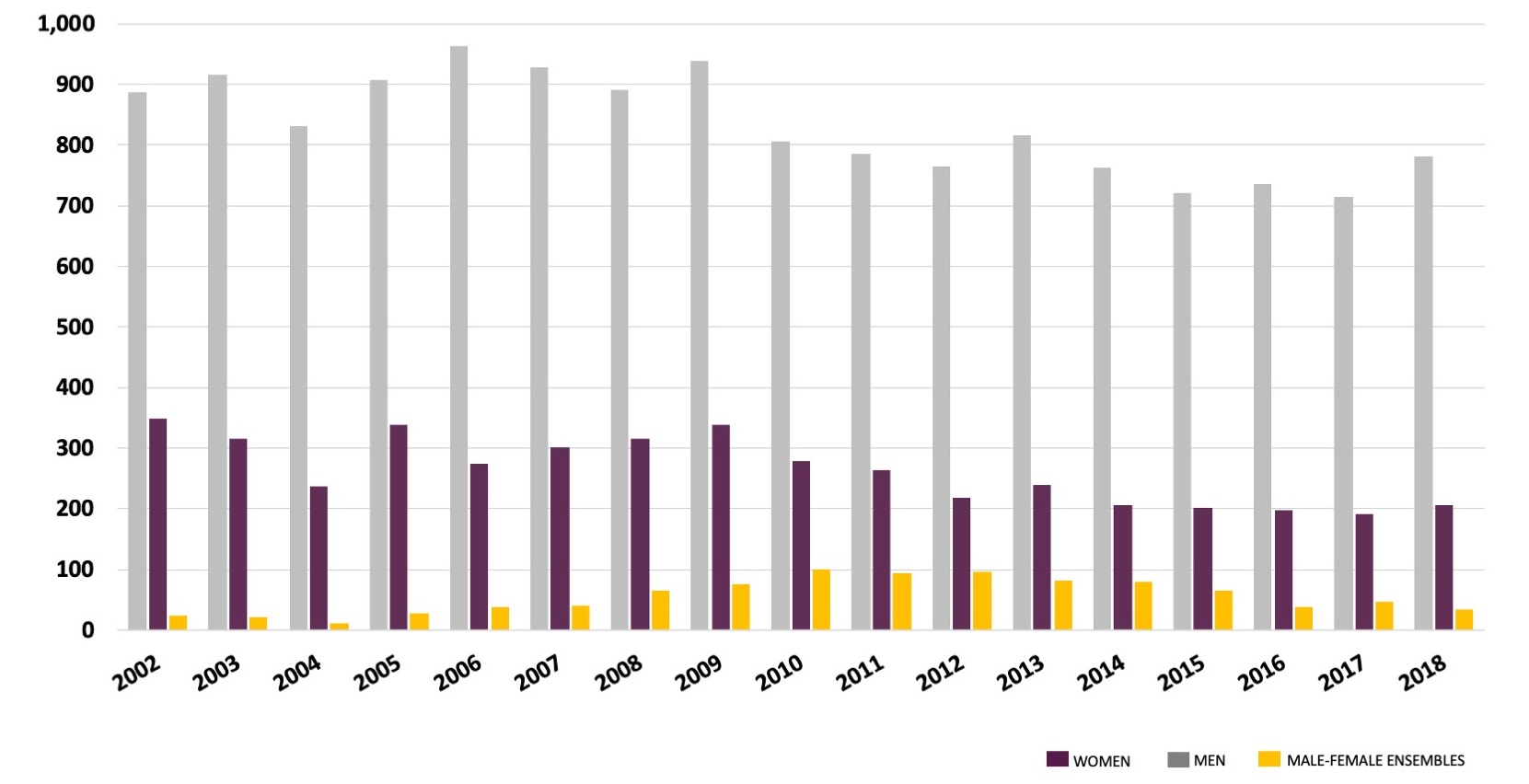

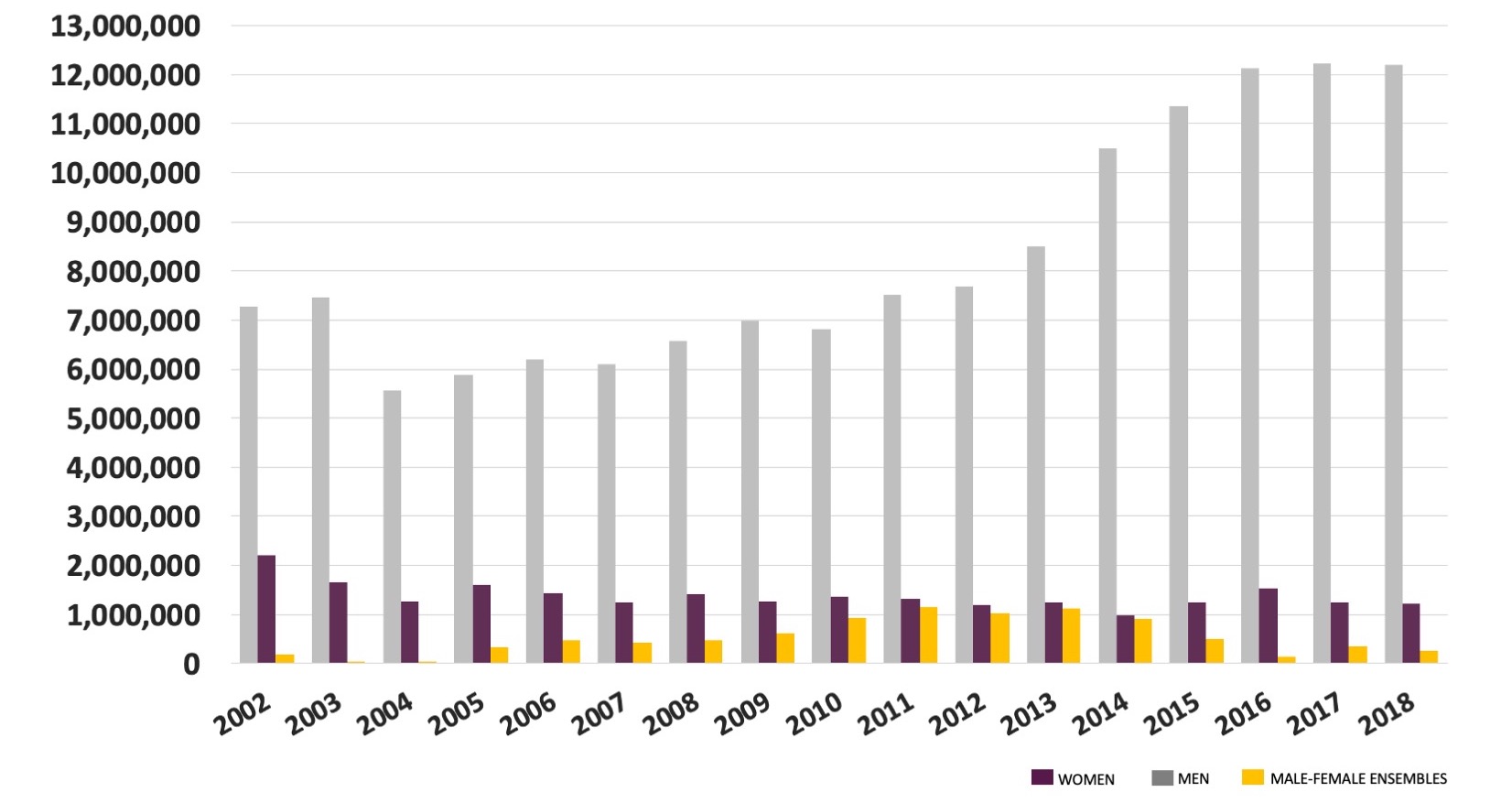

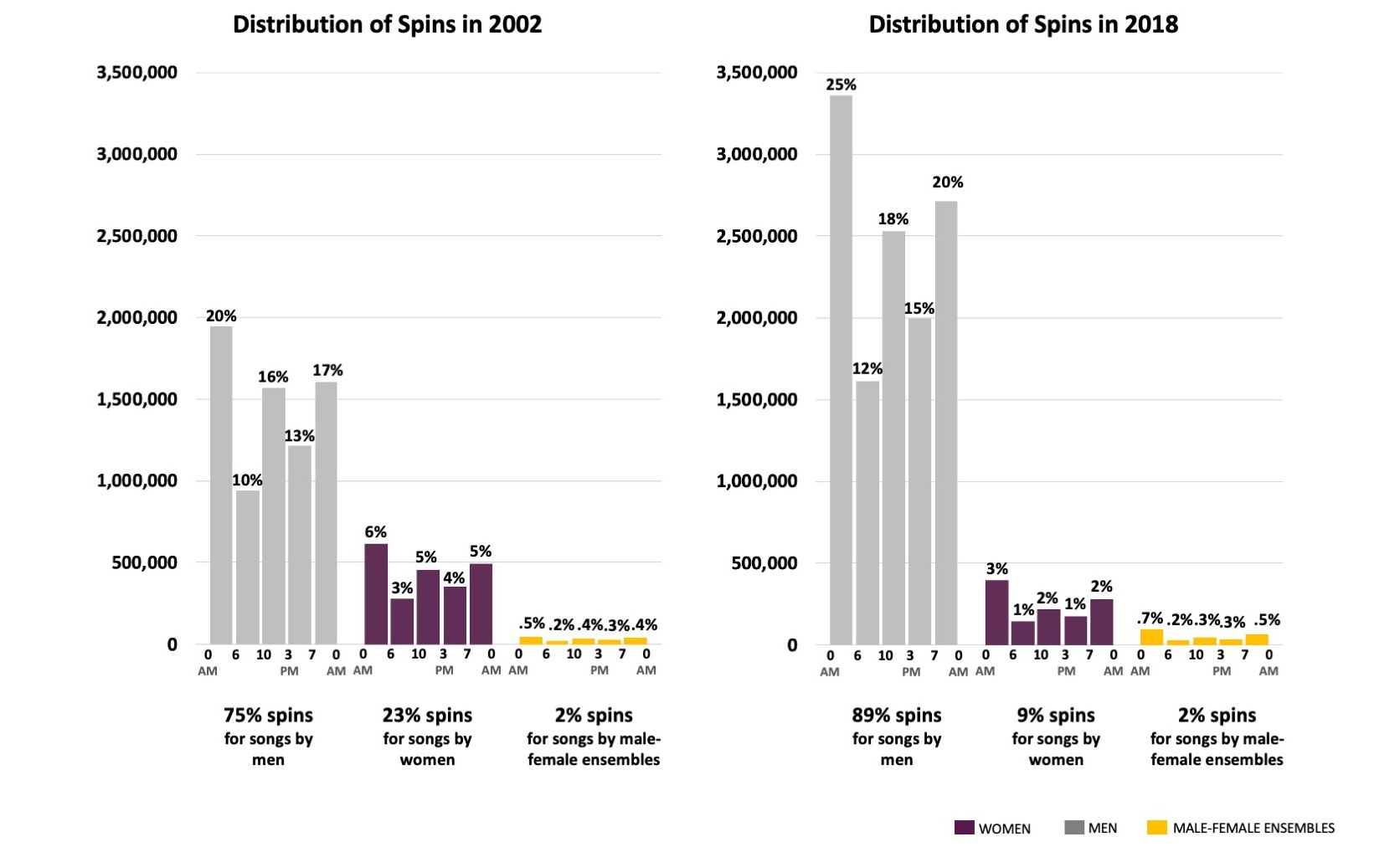

Theories of social remembering (Misztal 2003; Strong 2011) and digital redlining (Noble 2018) offer a critical framework for considering the credibility of big data within cultures that disadvantage and systematically ignore women. Reflecting on results of a data-driven analysis of Mediabase’s country airplay reports from 2000 to 2018, this paper considers the role of data in the process of shaping country music culture, and reframes our understanding of these reports as an instrument that systematically “remembers” some artists, while “casting away” or “forgetting” others. Over the course of this period, the number of songs by women played on country format radio declined 41.3% (Fig. 1). These reports map the evolving terrain of country music’s cultural space and have resulted in a system that pushes women to the margins: songs by women are played infrequently on country format radio (Fig. 2), with the majority of their airplay occurring in the overnights (Fig. 3) (Watson 2019a/b). As a result, songs by women are charting in declining numbers, peaking in the bottom positions of the weekly charts, and barely heard in radio’s peak daytime hours. Such practices impact black women more significantly (Watson 2020). In this way, the reports reveal a digital redlining of women, wherein programming practices are perpetuating inequalities by refusing high traffic times of day to already marginalized artists. More critically, this paper addresses the challenges of critiquing social remembering through public scholarship and reflects (as Marcia Chatelain [2016] does in her work) on my experiences of thinking and working in public digital spaces.

Gender has been a central dynamic of country music history and culture (Pecknold & McCusker 2016), wherein masculinity and femininity are invoked to define class boundaries, cultural tastes, institutional hierarchies, performance styles, and the evolution socially prescribed roles. With strong ties to conservatism and religion, country’s first female artists often appeared on stage with their husband or male family members, a constant reassurance for record-buyers that the social order in which females performed familial roles and habits of constancy and tradition endured in the genre (McCusker 2017). Following WWII, as female artists began taking a more prominent role on stage and behind the scenes, cultural institutions actively sought to censor lyrics in women’s songs if they were too “suggestive”, aggressive, or politically charged—a trend that has continued throughout the genre’s history (Bufwack & Oermann 2004; Keel 2004; Watson & Burns 2010). Behind the scenes, the country music industry has employed a strict quota system for female artists on radio playlists and label rosters (Penuell 2015), which has, in turn, limited their opportunities for participating within the mainstream of the industry as performer and songwriters.

Adopting methods for data-driven studies of popular music charts (Wells 2001; Lafrance et al 2011) and influenced by the concept of prosopography (Keats-Rohan 2007; Crompton & Schwartz 2018), this project has developed an approach for collecting and organizing music industry data in order to study how the biography of individuals shapes and is shaped by the genre’s cultural constructs. In order to address complex socio-cultural issues of equity and diversity in country music, it has developed a comprehensive dataset of all of the singles played on country format radio between 2000 and 2018, enhanced with biographic information about the lead and featured artists involved in performing the recorded tracks played on country radio to facilitate a vast range of queries about programming practices and their impact on weekly charts. In so doing, this project deconstructs the gender politics that have governed the genre and shows how big data has created and perpetuated gender inequalities and contributed to the continued marginalization and “forgetting” of female narrative voices within country music culture.

Figure 1. Distribution of unique songs by men, women and male-female ensembles played on country format radio between 2002 and 2018.

Figure 2. Distribution of spins for songs by men, women and male-female ensembles between 2002 and 2018 reveals a 40.2% increase in spins for male artists against a 44.8% decline in spins for songs by women.

Figure 3. Distribution of spins for songs by men, women and male-female ensembles across the five dayparts in country format radio programming in 2002 (left) and 2018 (right).

Appendix A

Bibliography

Bufwack, Mary A., and Robert K. Oermann. 2003. Finding Her Voice: Women in Country Music, 1800-2000. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; Country Music Founcation Press.

Chatelain, Marcia. 2018. “Is Twitter Any Place for a [Black Academic] Lady?” In Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and Digital Humanities, eds Elizabeth Losh and Jacqueline Wernimont, 173-184. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Crompton, Constance, and Michelle Schwartz. 2018. “Remaking HIstory: Lesbian Feminist Historical Methods in the Digital Humanities.” In Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and Digital Humanities, eds Elizabeth Losh and Jacqueline Wernimont, 131-56. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Keel, Beverly. 2004. “Between Riot Grrrl and Quiet Girl.” In A Boy Named Sue: Gender and Country Music, eds Kristine McCusker and Diane Pecknold, 155-77. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

Keats-Rohan, Katherine S.B.. 2007. Prosopography Approaches and Applications: A Handbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lafrance, Marc, et al. “Gender and the Billboard Top 40 Charts between 1997 and 2007.” Popular Music & Society 35/5: 557-70.

McCusker, Kristine M. 2017. “Gendered Stages: Country Music, Authenticity, and the Performance of Gender.” In The Oxford Handbook to Country Music, ed Travis D. Stimeling, 355-74. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Misztal, Barbra A. 2003. Theories of Social Remembering. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press.

Pecknold, Diane, and Kristine M. McCusker, eds. Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2016.

Penuell, Russ. 2015. “On Music and Scheduling.” Country Aircheck, 449: 1, 8, https://www.countryaircheck.com/pdfs/current052615.pdf.

Strong, Catherine. 2011. “Grunge, Riot Grrrl and the Forgetting of Women in Popular culture.” The Journal of Popular Music Culture 44/2: 398-416.

Watson, Jada. 2019a. “Gender Representation on Country Format Radio: A Study of Published Reports from 2000 to 2018.” Report prepared in consultation with WOMAN Nashville, https://bit.ly/gender-country-radio.

Watson, Jada. 2019b. “Gender Representation on Country Format Radio: A Study of Spins Across Dayparts (2002-2018).” Report prepared in consultation with WOMAN Nashville, https://bit.ly/gender-country-radio-tod-airplay.

Watson, Jada. 2020. “Inequality on Country Radio: 2019 in Review.” Report prepared in partnership with CMT’s EqualPlay Campaign, https://bit.ly/gender-country-radio-equalplay.

Watson, Jada, and Lori Burns. 2010. “Resisting Exile and Asserting Musical Voice: The Dixie Chicks Are ‘Not Ready to Make Nice’.” Popular Music 29/4: 325-50.

Wells, Allan. 2001. “Nationality, Race and Gender on the American Pop Charts: what Happened in the 90s?” Popular Music & Society 25: 221-31.