1. Abstract

This proposal examines the importance of visual representations to convey semantic shifts while presenting a work in progress concerning the diachronic study of modality in Latin.1

A visualisation is meant to aid the comprehension of data by taking advantage of our visual perception and its capacity to discern patterns, trends and atypical values (Heer et al. 2010: 59). A visual representation is more accessible, attractive and it can replace complex cognitive calculations. However, selecting the most efficient visualisation can be challenging, especially when conceiving it as a scholarly resource (see Jessop 2008) for the representation of abstract concepts. In our case we would need to:

condensate pages and pages of dictionaries and historical grammars;

add information to previous models to better convey the multidimensionality of modal semantic shifts;

update the traditional visualisation models incorporating motion, color and user interactivity.

The semantic map visualisation method was introduced by Haspelmath (2003)2 to describe and illustrate the multifunctionality patterns of linguistic elements. The semantic map appears as a geometric representation of functions connected together in a semantic space. Semantic maps were employed in various ways, cross-linguistically or on individual languages,3 and synchronically or diachronically.

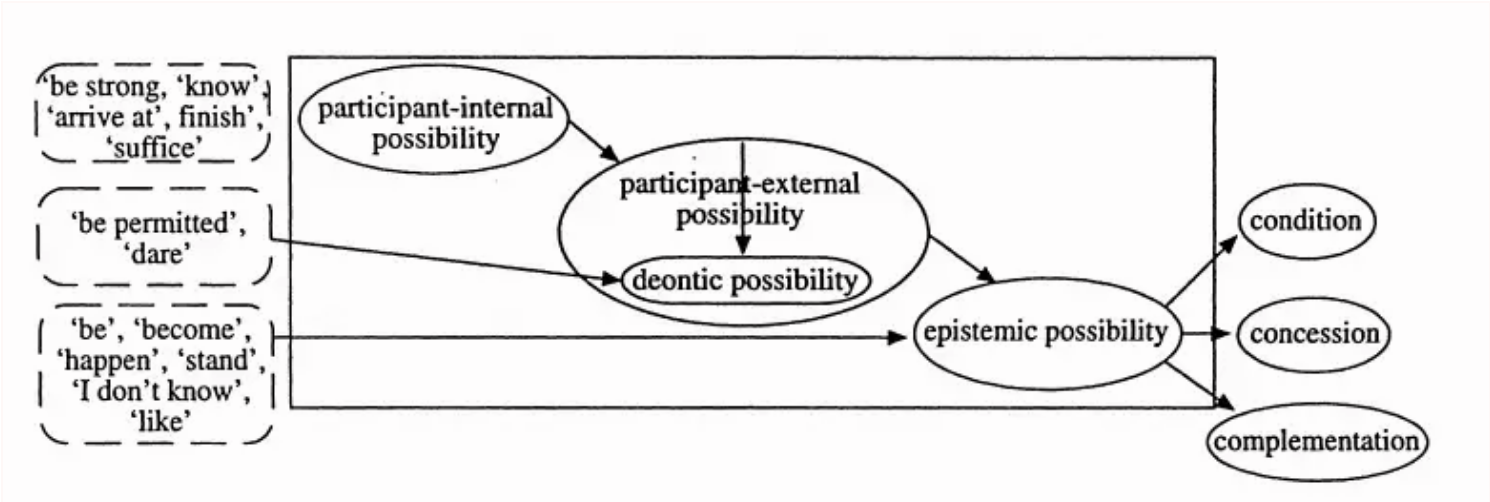

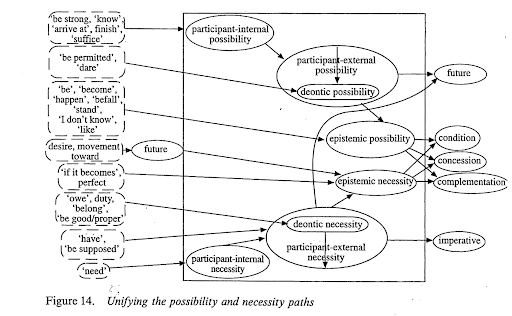

Van der Auwera and Plungian (1998) apply this resource to visually represent and predict universal patterns of modalisation.4 They build on the single patterns of modalisation for possibility and necessity of the cross-linguistic study by Bybee et al. (1994) (see Fig. 1), complementing them with lexical information from other languages. An overview of the modalisation and grammaticalisation paths is achieved by including pre- and post-modal meanings (Fig. 2).5

Fig. 1: “To possibility and beyond” (van der Auwera and Plungian 1998: 91).

Fig. 1: “To possibility and beyond” (van der Auwera and Plungian 1998: 91).

Fig. 2: “Unifying the possibility and necessity paths”: Example of a semantic map representing the shifts of possibility and necessity (van der Auwera and Plungian 1998: 98).

Fig. 2: “Unifying the possibility and necessity paths”: Example of a semantic map representing the shifts of possibility and necessity (van der Auwera and Plungian 1998: 98).

Our proposal follows this model but our aim is to produce a digital visualisation with these additional features:

Diachrony: Addition of a timeline to visualise when new meanings appear.

Synchrony: Visualisation of coexisting meanings based on position and shape.

Chronology: Addition of the etymological information available for each marker;6 enrichment of each meaning with its first attestation that is displayed by hovering the mouse over that concept.

Polyfunctionality: Working with empirical data does not imply unambiguous findings, therefore our proposal codifies multiple modal values of the same marker.

Multilingual versions: A map in the source language together with the English translation is available: users can change the language at will.

Legibility: Points 1-5 extend the contents of previous models. To guarantee legibility, certain information is color-coded and other pieces of information will appear by user demand. Colors, for instance, are employed to identify and distinguish pre-, post- and modal meanings. Users can bring out a specific path of modal shift just by clicking on one of the affected senses/steps. A combination of shape and position can render the coexistence of meanings.

We are currently working on the development of the semantic modal maps of some Latin modal markers. These maps were drafted based on the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (Thesaurusbüro München Internationale Thesaurus-Kommission 1900–), and are susceptible of change against corpus-based evidence. This work in progress is available at our website (http://woposs.unil.ch/semantic-modal-maps.php). Updates refining the visualization and/or adding more semantic maps are frequent. As part of the future work, we envisage the implementation of additional features: we plan to employ motion to visualise the modal path of a specific marker interacting with its chronological attestations. Also, we are conscious of the challenges that discernity of color entails for people with visual disabilities, thus we want to avoid the use of color as the only visual means of conveying certain information. Therefore, we plan to combine it with other visual cues, like texture. In addition, the size will be customizable and color contrast will be checked.7

The visualisations currently available were developed using Inkscape8 to create the basic SVG that will be enhanced by manually including the animation elements with a combination of JavaScript and CSS. The selection of open-source software guarantees an open development. Therefore, not only the results, but all the data and methods will be made publicly available, thus contributing to both the Open Data movement and Public Digital Humanities.

Even if the core of our work concerns Latin modality, the principles and techniques presented can be easily applied to any other language. We claim this model to be versatile: it would be useful to researchers, but also appropriate for vehiculating complex semantic concepts in an educational environment thanks to its readability and immediacy. Besides its possible implementation with languages other than Latin, any type of semantic shift could be visualised following our template. Semantic maps aid in the understanding of meaning so any fields working with natural language, like history or philology, would benefit from our results.

Notes

1 This study is part of the SNSF-funded project (SNSF n° 176778) A world of possibilities: Modal pathways over an extra-long period of time: the diachrony of modality in the Latin language (WoPoss). See more information in http://woposs.unil.ch. All the data and code of this project will be made available during the project lifespan (February 2019–January 2023) as open data.

2 For earlier conceptualizations of semantic maps see Hjelmslev (1963), Lazard (1981), Anderson (1982).

3 For both a single-language approach and a cross-linguistic one see François (2008).

4 Semantic maps had been already applied (amongst others) to tense and aspect (Anderson 1982), evidentiality (Anderson 1986), conditionals (Traugott 1985), voice (Croft et al. 1987).

5 The model by van der Auwera and Plungian (1998) and Bybee et al. (1994) has been applied by Magni to modal markers in Latin (2005).

6 The etymological information for Latin is taken from the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (1900–), de Vaan (2011), Ernout-Meillet (1932) and Meiser (1998).

7See https://webaim.org/resources/contrastchecker (consulted on 05/06/2020).

8Available at https://inkscape.org/ (consulted on 05/06/2020).

References

Anderson, Lloyd B. 1982. ‘The “Perfect” as a Universal and as a Language-Particular Category’. In Tense-Aspect: Between Semantics & Pragmatics. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 227–64.

———. 1986. ‘Evidentials, Paths of Change, and Mental Maps: Typologically Regular Asymmetries’. In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, edited by Wallace L. Chafe and Johanna Nichols, 273–312. Norwood, N.J: Ablex.

Auwera, Johan van der, and Vladimir A. Plungian. 1998. ‘Modality’s Semantic Map’. Linguistic Typology, 2 (1): 79–124.

Bybee, Joan L., Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect and Modality in the Languages of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/E/bo3683926.html.

Croft, William, Hava Bat-Zeev Shyldkrot, and Suzanne Kemmer. 1987. ‘Diachronic Semantic Processes in the Middle Voice’. In 7th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, 48:179–92.

de Vaan, Michiel. 2011. Etymological Dictionary of Latin. Leiden: Brill. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from https://brill.com/view/title/12612

Ernout, Alfred, and Antoine Meillet. 1932. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine: histoire des mots. Paris: Klincksieck.

François, Alexandre. 2008. ‘Semantic Maps and the Typology of Colexification: Intertwining Polysemous Networks across Languages’. In From Polysemy to Semantic Change: Towards a Typology of Lexical Semantic Associations, 163–215. Studies in Language Companion 106. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00526845/document.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2003. ‘The Geometry of Grammatical Meaning: Semantic Maps and Cross-Linguistic Comparison’. In The New Psychology of Language, 217–48. Psychology press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410606921-11.

Heer, Jeffrey, Michael Bostock, and Vadim Ogievetsky. 2010. ‘A Tour through the Visualization Zoo’. Communications of the ACM 53 (6): 59. https://doi.org/10.1145/1743546.1743567.

Hjelmslev, Louis. 1963. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. University of Wisconsin Press.

Jessop, Martyn. 2008. ‘Digital Visualization as a Scholarly Activity’. Literary and Linguistic Computing 23 (3): 281–93. doi:10.1093/llc/fqn016.

Lazard, Gilbert. 1981. ‘La Quête Des Universaux Sémantiques En Linguistique’. Actes Sémiotiques (Bulletin) 19: 26–37.

Magni, Elisabetta. 2005. ‘Modality’s Semantic Maps. An Investigation of Some Latin Modal Forms’. Journal of Latin Linguistics 9 (1): 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1515/joll.2005.9.1.325.

———. 2010. ‘Mood and Modality’. In New Perspectives on Historical Latin Syntax. Constituent Syntax: Adverbial Phrases, Adverbs, Mood, Tense, edited by Philip Baldi and Pierluigi Cuzzolin, 2:193–275. Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs 180. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Meiser, Gerhard. 1998. Historische Laut- und Formenlehre der lateinischen Sprache. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Thesaurusbüro München Internationale Thesaurus-Kommission, ed. (1900-). Thesaurus Linguae Latinae. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 1985. ‘Conditional Markers’. In Iconicity in Syntax, 289–307.