1. Abstract

Technical Note

A PDF version of this contribution is available at Humanities Commons: https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:30439 Several versions of this contribution in structured formats, including figures and bibliographical data, are available from Zenodo: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3893428

Panel Overview

The "replication crisis" that has been raging in fields like Psychology (Open Science Collaboration 2015) or Medicine (Ioannidis 2005) for years has recently reached the field of Artificial Intelligence (Barber 2019). One of the key conferences in the field, NeurIPS, has reacted by appointing 'reproducibility chairs' in their organizing committee 1. In the Digital Humanities, and particularly in Computational Literary Studies (CLS), there is an increasing awareness of the crucial role played by replication in evidence-based research. Relevant disciplinary developments include the increased importance of evaluation in text analysis and the increased interest in making research transparent through publicly accessible data and code (open source, open data). Specific impulses include Geoffrey Rockwell and Stéfan Sinclair's re-enactments of pre-digital studies (Sinclair and Rockwell 2015) or the recent replication study by Nan Z. Da (Da 2019). The paper has been met by an avalanche of responses that pushed back several of its key claims, including its rather sweeping condemnation of the replicated papers. However, an important point got buried in the process: that replication is indeed a valuable goal and practice. 2As stated in the Open Science Collaboration paper: "Replication can increase certainty when findings are reproduced and promote innovation when they are not" (Open Science Collaboration 2015, 943).

As a consequence, the panel aims to raise a number of issues regarding the place, types, challenges and affordances, both on a practical and on a policy or community level, of replication in CLS. Several impulse papers will address key aspects of the issue: recent experience with attempts at replication of specific papers; policies dealing with replication in fields with more experience in the issue; conceptual and terminological clarification with regard to replication studies; and proposals for a way forward with replication as a community task or a policy issue.

Contribution 1: "A typology of replication studies", by Christof Schöch

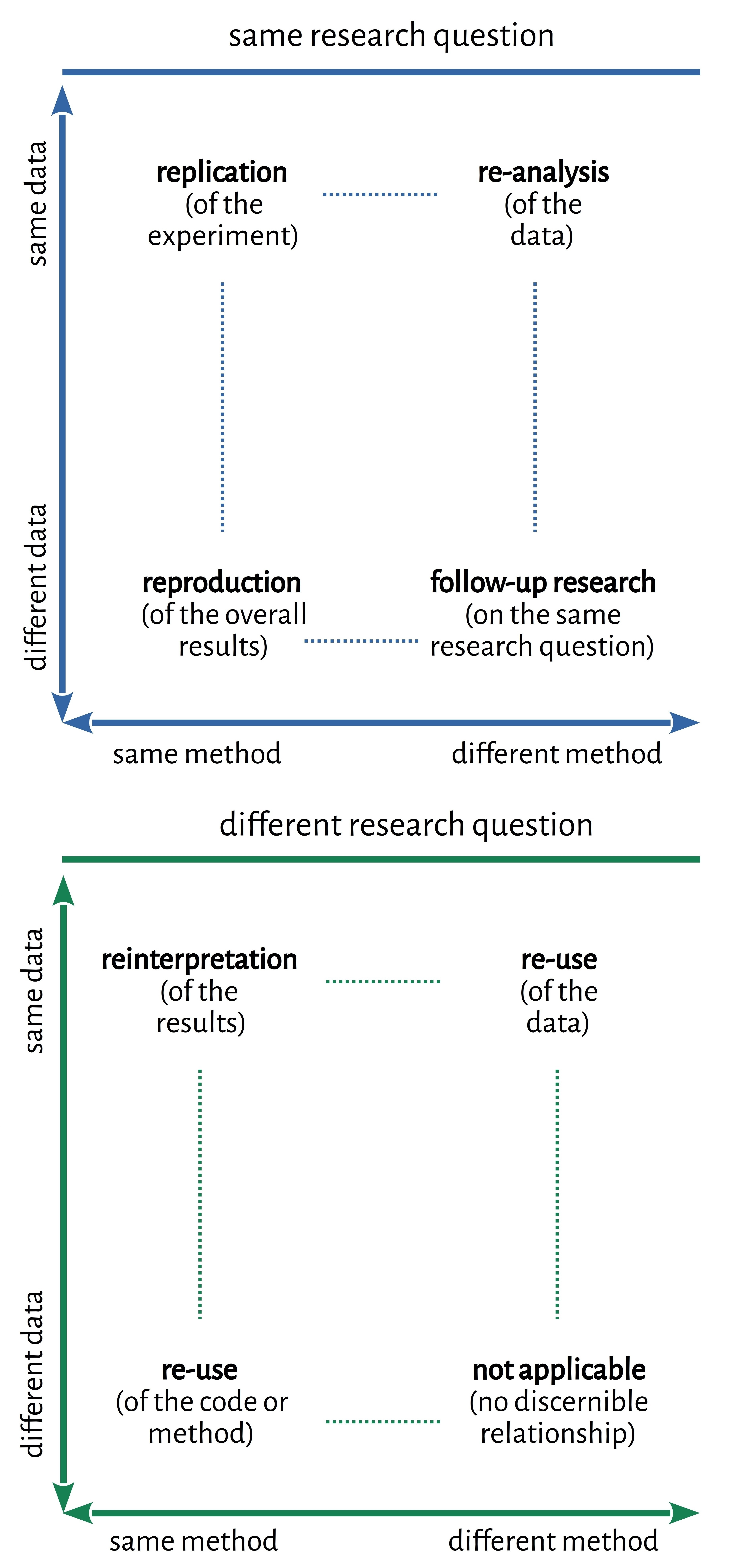

This contribution aims to provide orientation about the range of existing replication studies, based on a simple typology. The typology describes the relationship between an earlier study and its replication in terms of four key variables: the research question, the method of analysis (including the implementation of that method) and the dataset used. 3 For each of these variables, a replication study can attempt to operate either in the same way as the previous study, or in a different way. Note that the typology is not meant to establish these distinctions in a purely binary fashion: rather, as data or methods are never entirely identical or completely different from the earlier study, the extreme points in the typology are meant to open up a gradient of pratices. In addition (and this aspect might be unique to the Digital Humanities), replication studies can be described as involving crossing the boundary between non-digital and digital research or between qualitative and quantitative research.

Figure 1: Typology of repeating research

At the most fundamental level, such a typology structures the field and provides a clearly-defined terminology and systematic relations between the various types. For example, replication vs. reproduction or re-analysis vs. follow-up research. Such a shared understanding is useful because each type of replication study comes with its own objectives, requirements and challenges as well as their own place and function in the research process. A replication study strictly repeating key aspects of an earlier study will be most useful in reviewing and quality assessment, while follow-up research more loosely modeled after an earlier study may instead have important methodological implications or lead to knew domain knowledge. This is true despite the fact that in reality, there is more to consider than a few binary categories when describing a given replication study.

But understanding replication through such a typology can have an impact on the field of DH in a number of additional ways. It can provide guidance when publishing research and help clarify what needs to be provided (in terms of data, code and contextualization in prose) in order for a study to be amenable to a specific type of replication. It can help assess the merits and limitations of a given replication study to assess whether, given the stated objectives of the authors, they have employed a suitable type of replication strategy. And it can support designing a replication study and clarify what data, code and contextual information needs to be obtained or reconstructed in order to perform a specific type of replication. 4

Beyond this, such a typology can contribute to better define the relationship between replication in the strict sense and related efforts like benchmarking and evaluation studies. Finally, because such a typology makes it easier to identify similar studies across disciplinary boundaries, it may help us as a field learn more quickly from other fields with a longer tradition in (specific types of) replication studies. In this way, such a typology of replication studies can contribute to establishing replication as a well-understood part of Computational Literary Studies.

Contribution 2: "Replication to the Rescue: Funding Strategies", by Karina Van Dalen-Oskam

The Dutch Research Council (NWO) is the first funding agency to take the initiative for a pilot programme for Replication Studies. Their aim is "to encourage researchers to carry out replication research. NWO wants to gain experience that can lead to insights into how replication research can be effectively included in research programmes. That experience should also lead to insights into and a reflection on the requirements that NWO sets for research in terms of methodology and transparency." 5The first two rounds of funding were in 2017 and 2018, and were aimed at the Social Sciences and Medical Sciences. In the third round in 2019, the Humanities were included.

This was done after a heated discussion in Nature between Rik Peels and Lex Bouter (chair of the Replication Studies Programme Committee) on the one hand, and Bart Pender, Sarah de Rijcke and J. Britt Holbrook on the other. Peels and Bouter (2018) started of with a note titled "Humanities need a replication drive too". De Rijke and Penders (2018), both scholars from Science and Technology Studies, countered with the call to "Resist calls for replicability in the humanities". They argue that quality criteria are crucially different in the humanities and the sciences. 6

NWO went ahead with including the humanities in the call for replication studies, stating they are aware that not all humanities research is suitable for replication. NWO "expresses no preference or opinion about the value of various methods of research. Where possible it wants to encourage and facilitate the replication of humanities research: this should certainly be possible in the empirical humanities." 7In March 2020, seven proposals were awarded funding, but none of these can be called typical Humanities projects. 8How many submissions were received from humanities applicants - did scholars indeed resist, as Pender and De Rijcke advised? And in a wider context: How do Dutch Humanities scholars evaluate the new possibility? And does this agree with the reception in the growing and very active Dutch Digital Humanities community?

In my short impulse paper, I will reflect on what we can learn from the explicit invitation to the humanties to apply for funding for replication studies. What does this tell us about the status of humanities research in the Netherlands, and more specifically about the role of the Digital Humanities? I will pay special attention to the opportunities these developments may have for Computational Literary Studies. Should we consider the situation as "Funding Strategies to the Rescue: Replication", so a turning around of the title of my talk?

Contribution 3: "Replication of quantitative and qualitative research - a case study", by Fotis Jannidis

Literary studies always had an empirical side - 'empirical' in the broader sense, that claims and counterclaims are substantiated by referring to specific parts of texts. These text segments are regarded as indicators which in their sum make a more general point plausible, for example the use of specific terms to validate a hypothesis about a text. Therefore, the concept of replication warrants a wider understanding in Computational Literary Studies. The prototypical center is the quantitative replication of quantitative research, but it also includes quantitative replication of qualitative philological research: Using the same indicators to validate the same hypothesis but moving the research into an empirical framework. Seen in the context of the discussion of mixed methods, this is a specific case of ‘triangulation’. Triangulation refers to “the application of different data analysis methods, different data sets, or different researchers’ perspective to examine the same research question or theme” (Bergin 2018, 29). But here, data sets and data analysis methods overlap strongly, while the research framework is changed from hermeneutic to quantitative.

Our case study is an attempt to replicate research on the complexity of language in German dime novels, published by Peter Nusser (Nusser 1981), and it demands both kinds of replication. Nusser describes the language of dime novels on three levels: vocabulary, syntax, and phrases. The work on vocabulary and syntax is quantitative, while the analysis of phrases is qualitative. The replication of the quantitative parts is made more difficult by the fact that the results which Nusser reports have actually been produced by another author in the context of an unprinted exam thesis which seems to be lost for the moment. So a lot of information is missing, and we can only make educated guesses: the exact corpus design (for high literature only the authors are given and for dime novels only the series), the strategies of tokenization and sentence splitting, the exact formula for calculating specific values, etc. The qualitative research is enumerating many phrases which are seen as examples of clichés and there is no explicit comparison with high literature. So a quantification must try to operationalize the concept of cliché and then compare retrieval results between dime novels and high literature.

As is well known in Computational Literary Studies, operationalization as an instance of formal modeling usually covers some aspects that are part of the intuitive notion, while others are excluded for the time being and it is one goal to reduce the loss (Moretti (2013); for a counterposition see Underwood (2019, 181)). In a replication, the loss may be responsible for the difference in outcome. In view of all these difficulties it could seem an unnecessary endeavor to replicate the research, but Nusser’s study had a huge influence on the assessment and evaluation of popular literature in German studies for almost four decades.

Contribution 4: "Reliable methods for text analysis", by Maria Antoniak and David Mimno

If we are to make reproducible computational claims about literary texts, we need methods that lend themselves to robustness and reliability. Here we focus on the case study of word embeddings, which analyze collections of documents and produce numeric representations of words. Although these methods are powerful, they are also at high risk for problems with reproducibility: they are complicated enough to be essentially "black boxes", yet they are also known to be highly sensitive to text curation choices, parameter settings, and even random initializations (Antoniak and Mimno 2018). How can we assure researchers and their audiences that seemingly small changes would not alter or even reverse their findings?

Embedding vectors are useful for their ability to operationalize thick cultural concepts. For example, the resulting vectors have been used to measure shifts in word meaning over time and geographic areas (e.g. Hamilton, Lescovec, and Jurafsky (2016); Kulkarni, Perozzi, and Skiena (2016)). Several studies have shown that embeddings can encode gender biases by probing embedding spaces using carefully chosen seed words (Gordon and Van Durme (2013); (Bolukbasi et al. 2016a); Caliskan Islam, Bryson, and Narayanan (2016)). Subsequent work in natural language processing has focused on removing biases from an embedding model (Bolukbasi et al. (2016b); Sutton, Lansdall, and Cristianini (2018)). In this context, the concern is the downstream impact of bias on systems that use embeddings, but similar work can also be motivated from an upstream perspective, as a means of studying bias in collections.

Researchers from the humanities and social sciences use embeddings to provide quantitative answers to otherwise elusive political and social questions about the training corpus and its authors (e.g. Kozlowski, Taddy, and Evans (2019)). These bias detection techniques were originally intended to measure the bias encoded in a trained embedding; they were not originally tested to measure the bias of a corpus and make comparisons between corpora.

We probe the stability of these measurements by testing two popular bias detection methods ( Bolukbasi et al. (2016a); Caliskan Islam, Bryson, and Narayanan (2016)) on sets of automatically constructed seed sets. These sets were constructed by randomly selecting a target term and then including its N nearest neighbors in the set; this process more closely approximates a real seed set, constructed by a scholar interested in a particular concept, than a random set of seeds. We find that bias detection techniques via word embeddings are susceptible to variability in the seed terms, in both their order (alternative pairings of seeds from two sets can significantly change the ability of the method to capture a single bias subspace) and semantic similarity (the more similar seeds set are to each other, the more difficult it is to measure their biases). If done carefully, bias detection using embeddings is feasible even for small, subdivided collections and can provide a promising tool for differential content analysis, but we encourage error analysis of the seed terms.

We further highlight a central inconsistency in these bias detection methods. While these methods seek to measure biases in datasets, the researcher-selected seeds themselves can contain a variety of biases. For example, the seeds used for racial categories often include lists of names that are "African American" or "European." Such lists can be both reductive and essentializing. In addition, some seed sets contain confounding terms, e.g., contain a gendered term in a seed set for "domestic work" that is then used to measure gender bias. If the seed set for "domestic work" appears closer to the gender that it contains, it will be impossible to say whether that bias exists because of the training corpus or because of the inclusion of the gendered seed.

This case study highlights the reversal in perspectives when techniques from natural language processing and machine learning are re-purposed for studies of specialized datasets. Some working assumptions from the machine learning community (e.g. large size of training set) are broken in the humanities context, where datasets are non-expandable and are the primary focus of the study, rather than a generalized training set for downstream applications. The stability and robustness of these repurposings should not be assumed but rather should be reanalyzed for the particular new contexts.

Bibliography

Antoniak, Maria, and David Mimno. 2018. “Evaluating the Stability of Embedding-Based Word Similarities.” Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 6. https://transacl.org/ojs/index.php/tacl/article/view/1202.

Barber, Gregory. 2019. “Artificial Intelligence Confronts a ‘Reproducibility’ Crisis.” Wired, 2019. https://www.wired.com/story/artificial-intelligence-confronts-reproducibility-crisis/.

Bergin, Tiffany. 2018. An Introduction to Data Analysis. Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Methods. London: Sage.

Bolukbasi, Tolga, Kai-Wei Chang, James Zou, Venkatesh Saligrama, and Adam Tauman Kalai. 2016a. “Man Is to Computer Programmer as Woman Is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings.” In NIPS. https://arxiv.org/abs/1607.06520.

Bolukbasi, Tolga, Kai-Wei Chang, James Y. Zou, Venkatesh Saligrama, and Adam Tauman Kalai. 2016b. “Quantifying and Reducing Stereotypes in Word Embeddings.” In Data4Good: Machine Learning in Social Good Applications, edited by Kush R. Varshney. http://arxiv.org/abs/1606.06121.

Caliskan Islam, Aylin, Joanna J. Bryson, and Arvind Narayanan. 2016. “Semantics Derived Automatically from Language Corpora Necessarily Contain Human Biases.” In CoRR. http://arxiv.org/abs/1608.07187.

Da, Nan Z. 2019. “The Computational Case Against Computational Literary Studies.” Critical Inquiry 45 (3): 601–39. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/702594.

De Rijke, Sarah, and Bart Penders. 2018. “Resist Calls for Replicability in the Humanities.” Nature 560 (29). https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05845-z.

Deckker, Harrison, and Paula Lackie. 2016. “Technical Data Skills for Reproducible Research.” Edited by Lynda M. Kellam and Kristi Thompson. Databrarianship: The Academic Data Librarian in Theory and Practice. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8qb2q8fk.

Gómez, Omar S., Natalia Juristo, and Sira Vegas. 2010. “Replication, Reproduction and Re-Analysis: Three Ways for Verifying Experimental Findings.” In RESER ’2010 Cape Town.

Gordon, Jonathan, and Benjamin Van Durme. 2013. “Reporting Bias and Knowledge Acquisition.” In Proceedings of the 2013 Workshop on Automated Knowledge Base Construction. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/2509558.2509563.

Hamilton, William L., Jure Lescovec, and Dan Jurafsky. 2016. “Diachronic Word Embeddings Reveal Statistical Laws of Semantic Change.” Edited by Hamilton, Jure Lescovec, and Dan Jurafsky. CoRR. http://arxiv.org/abs/1605.09096.

Hüffmeier, Joachim, Jens Mazei, and Thomas Schulte. 2015. “Reconceptualizing Replication as a Sequence of Different Studies: A Replication Typology.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 81–92. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103115001195.

Ioannidis, J.A. 2005. “Contradicted and Initially Stronger Effects in Highly Cited Clinical Research.” JAMA, no. 294/2: 218–28. https://doi.org/https://doi:10.1001/jama.294.2.218.

Kozlowski, Austin C., Matt Taddy, and James A. Evans. 2019. “The Geometry of Culture: Analyzing Meaning through Word Embeddings.” American Sociological Review 84 (5). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0003122419877135.

Kulkarni, Vivek, Bryan Perozzi, and Steven Skiena. 2016. “Freshman or Fresher? Quantifying the Geographic Variation of Internet Language.” In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Web and Social Media. http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM16/paper/view/13121.

Moretti, Franco. 2013. “‘Operationalizing’: Or, The Function of Measurement in Modern Literary Theory.” Stanford Literary Lab Pamphlet 6. https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet6.pdf.

Nusser, Peter. 1981. Romane für die Unterschicht. Der Groschenroman und seine Leser [1973]. Stuttgart: Metzler.

Open Science Collaboration. 2015. “Estimating the Reproducibility of Psychological Science.” Science, no. 349 (6251). https://science.sciencemag.org/content/349/6251/aac4716.

Peels, Rik, and Lex Bouter. 2018. “Humanities Need a Replication Drive Too.” Nature 558 (372). https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05454-w.

Peels, Rik, and Lex Bouter. 2018a. “Replication Is Both Possible and Desirable in the Humanities, Just as It Is in the Sciences.” LSE Impact Blog, 2018. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2018/10/01/replication-is-both-possible-and-desirable-in-the-humanities-just-as-it-is-in-the-sciences/.

Peels, Rik, and Lex Bouter. 2018b. “The Possibility and Desirability of Replication in the Humanities.” Palgrave Communications 4 (95). https://science.sciencemag.org/content/349/6251/aac4716.

Pender, Bart, J. Britt Holbrook, and Sarah De Rijke. 2019. “Rinse and Repeat: Understanding the Value of Replication across Different Ways of Knowing.” Publications 2019 7 (3): 1–15. https://ideas.repec.org/a/gam/jpubli/v7y2019i3p52-d249307.html.

Schöch, Christof. 2017. “Wiederholende Forschung in Den Digitalen Geisteswissenschaften.” In Konferenzabstracts DHd2017: Digitale Nachhaltigkeit, edited by DHd-Verband. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.277113.

Sinclair, Stéfan, and Geoffrey Rockwell. 2015. “Epistemologica.” 2015. https://github.com/sgsinclair/epistemologica.

Sutton, Adam, Thomas Lansdall, and Nello Cristianini. 2018. “Biased Embeddings from Wild Data: Measuring, Understanding and Removing.” In Advances in Intelligent Data Analysis XVII. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01768-2\_27.

Underwood, Ted. 2019. Distant Horizons: Digital Evidence and Literary Change. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Notes

1. See: https://nips.cc/Conferences/2019/Committees.

2. For a selection of responses, see relevant contributions to Cultural Analytics: https://culturalanalytics.org/articles?tag=replication

3. For an earlier iteration of the typology, see Schöch (2017). For typologies in other fields, see Gómez, Juristo, and Vegas (2010) and Hüffmeier, Mazei, and Schulte (2015).

4. A practice-oriented guide is Deckker and Lackie (2016).

5. See: https://www.nwo.nl/en/research-and-results/programmes/replication+studies. Call for applications:

https://www.nwo.nl/en/funding/our-funding-instruments/sgw/replication-studies/replication-studies.html.

6. The discussion was continued in (Peels and Bouter 2018b), Peels and Bouter (2018a) and in Pender, Holbrook, and De Rijke (2019).

7. See: https://www.nwo.nl/en/news-and-events/news/2019/03/third-round-in-pilot-replication-studies-now-includes-the-humanities.html.

8. See: https://www.nwo.nl/en/research-and-results/programmes/magw/replication-studies/awards-2019.html.