1. Abstract

This paper is based on HAIRO, a Franco-Romanian project for creating a library of Romanian Hajdouk novels in an XML/TEI format (see https://proiectulbrancusihairo.wordpress.com/home-1/). Hajdouks were outlaws living in the woods, that fascinated the public in the second half of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century, both for their cruelty and their sense of justice. Between 1840 and 1920, they appear in almost 12% of the Romanian novels, with at least 40 titles specifically dedicated to this picturesque character.

Our main concern is “the place-making mediated by the text”, and more precisely the creation of a Hajdouk space; in a rural Romania, structured by clear and stable relationships between spaces, their nomadic way of life constitutes a disrupting force, and we are looking at if and how this reflects in the novels. Much along the lines of (Hay and Butterworth 2019), our work focuses less on the “indexical relationship to the physical world”, and more on the ways in which the texts create their own spatiality.

In the first part, we discuss the adaptation of Pustejovsky’s ISO metamodel (2014, 2019) to operate what we call a “basic annotation” of our set of novels. Faced with the specificities of our texts, we have defined not two, but seven types of spatial entities: toponyms, places, paths, zones, vehicles, topical spaces and potential spaces. The two last categories are the most salient difference between our annotation schema and the previous existing ones, and we advocate their interest in literary contexts, where “the other world” or “in his bosom” are frequently mentioned, to quote but two examples from a very rich list.

We further characterize the spaces as “absolute” or “relative”. For this “basic annotation”, we have renounced to define other types of relations, such as orientation, movement or metrics.

The annotation exercise took place in two phases. In a first, exploratory round, we have worked on XML files, and implemented our schema as a feature structure in TEI. In a second round, we have configured a BRAT server and started by measuring the inter-annotator agreement on a set of 10 samples of about 1000 words (see results in Galleron et al., forthcoming). In a third phase, currently under development, we proceed to the actual annotation of texts, using a place names dictionary to pre-annotate. Another path currently explored is that of the syntactic tagging of phrase constituents: since a large part of our space entities appear to assume a function of circumstantial complement of place, they could be spotted with a specialized dependencies tagger. However, the first experiences in this respect are quite disappointing, and all the more so they have been conducted on samples in French – results will probably be worse on Romanian samples, since Romanian is a language less equipped with NLP tools. Please note that usual NER systems (Stanford, Spacy library, etc.) do not work, or give very poor results, on Romanian texts. For all these reasons, manual annotation still appears as the best way to go, in spite of being extremely time consuming.

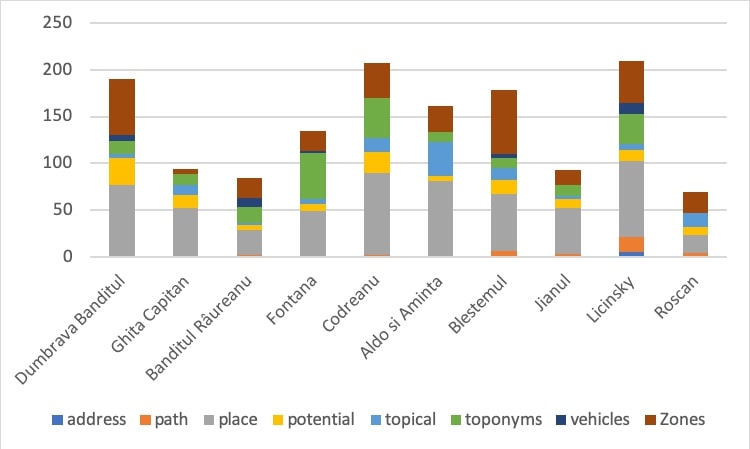

To date, the repartition of the annotations per type, as indicated in figure 1, confirms that looking at toponyms only, with a NER/ NEL approach, fails to capture a large part of the placemaking process in a novel. Also, two major categories of novels seem to appear with regards to the writing of the space, one constituted by the texts in which places and zones are in even proportions, the other gathering novels in which places are dominant, to the detriment of zones.

Figure 1. Annotations per type in a selection of novels

In addition, categories “paths” and “vehicles” seem to be discriminant between two other types of fiction. Indeed, while the number of annotations remains quite low in both cases, they allow to identify certain novels as outliers, with lots of spatial changes, as opposed to the major part of novels that appear finally more “static”, and privileging scenes and summaries of the action. This is somewhat surprising, since we expected all our Hajdouk novels to pertain to the second category. We are currently trying to understand if the difference is motivated by the specific style of certain authors, the taste of an era, or it genuinely points towards a generic specificity within our corpus;

Bibliography

Bodenhamer, David J.; Corrigan, John; Harris, Trevor M., Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives, Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 2015.

Bodenhamer, David J.; Corrigan, John; Harris, Trevor M., The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010, p. 109-123, muse.jhu.edu/book/26710.

Dic?ionarul cronologic al romanului românesc, Bucure?ti, Editura Academiei Române, 2003.

Galleron, Ioana, Patras, Roxana, Gradinaru, Camelia, Mélanie-Bécquet, Frédérique « À la recherche des haïdouks. L’annotation des entités spatiales dans un corpus de romans roumains du XIXe siècle », submitted to Revue des humanités numériques Humanistica, 2020.

Hay, Duncan, Butterworth, Alex (2019) “Spatial allusion, temporal recurrence and cognitive uncertainty: visualising chronotopic structure in a literary text”, DH2019 Book of abstracts.

Pustejovsky, James, Lee, Kiyong, Bunt, Harry (2019) “The Semantics of ISO-Space”, ISO committee draft for the revision of ISO (2014), https://let.uvt.nl/general/people/bunt/docs/PustejovskyLeeBunt_ISO-Space_ISA-15.pdf