1. Abstract

The Tribesourcing Southwest Film Project seeks to “tribesource” counter-narrations for educational films about the Native peoples of the Southwestern U.S. These films originate from the American Indian Film Gallery, a collection awarded to the University of Arizona in 2011.

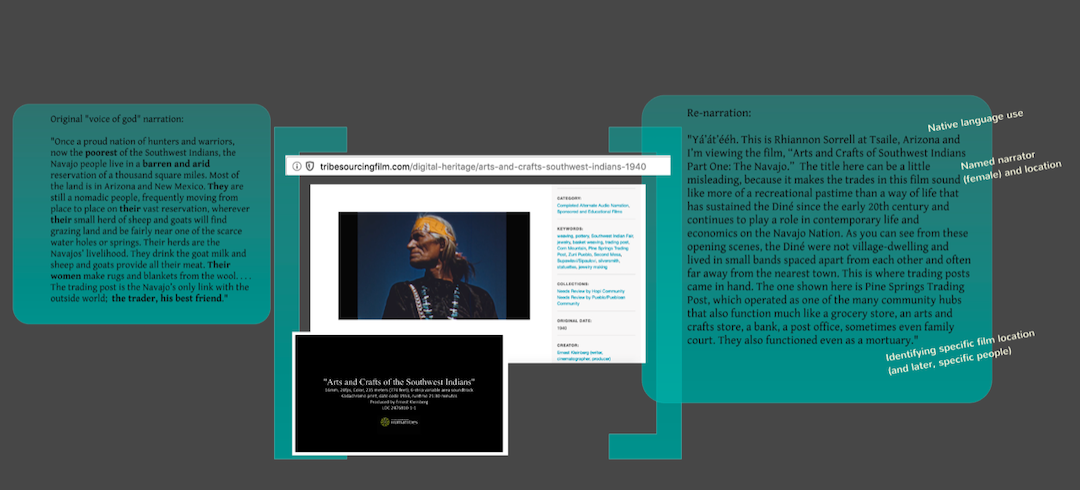

They were made in the mid-20th century for the K-12 educational and television markets and reflect mainstream cultural attitudes of the day. Often the male “voice of God” narration pronounces meaning that is inaccurate or disrespectful, but the visual narratives are for the most part quite remarkable. At this historical distance, many of these films have come to be understood by both Native community insiders and outside scholars as documentation of cultural practices and lifeways—and, indeed, languages—that are receding as practitioners and speakers pass on. This project seeks to rebalance the historical record through digital intervention, intentionally shifting emphasis from external perceptions of Native peoples to the voices, knowledge, and languages of the peoples represented in the films by participatory recording of new narrations for the films. Native narrators record new narrations for the films, actively decolonizing this collection and performing information redress through the merger of vintage visuals and new audio. We propose to report on work-in-progress and future plans.

“Tribesourcing” obviously plays off the term “crowdsourcing,” but intentionally places historical materials with the exact peoples they represent so they may address the untold or suppressed story. Furthermore, Native narrators are compensated for their contributions, and identified: aspects that temper what might otherwise be perceived as another example of soliciting “free” and “invisible” labor from communities of color. Films in this project are streamed through the interface of our chosen content management system, Mukurtu, beside alternate narrations from within the culture in English and in Native languages. This method allows for an unmediated approach to identification of people, places, practices, vocabulary and stories that might otherwise be lost, as well as providing a rich, community-based metadata record for each film. Taking a small step toward cultural repatriation of content, tribesourcing as a methodology is guided by the Protocols for American Indian Archival Materials (2006) and the groundbreaking work of Margaret Kovach (2010) and Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012).

The process of identifying narrators is best handled within the communities.Thus, paid Tribal Narration Coordinators perform the essential function of recruiting and working with narrators on-site. Rhiannon Sorrell serves in this position at Diné College in Tsaile, Arizona. Having done the very first counter-narration as proof-of-concept for the Tribesourcing project, Sorrell is well-equipped to explain the project to potential narrators and oversee recordings and payments for narrators. She will give her perspective in our presentation.

From its inception, this project has existed at the crossroads of indigenous studies, film and media studies, and public digital humanities. The content resides with our Native partners; dissemination and access occur through this digital humanities project that we steward. Close collaboration with Native Nations helps to ensure cultural competency in information management, and Mukurtu’s incorporation of a digital toolset (Google maps, HTML5 video and audio players, linked data capabilities, and integration with third-party streaming platforms) afford us the means of reaching a broad user base in Indian Country, where geographical distances often inhibit access to primary materials. The new narrations, metadata, dictionary, and Traditional Knowledge Labels, when placed literally alongside films themselves, help to subvert the films’ original narrative conventions, and provoke the viewer to question the visual and spoken rhetoric (Posner, 2016). As a film preservation project, we also acknowledge “‘precious fragments’ of indigenous knowledge are increasingly held captive in obsolete audio-visual media formats” (Lawson, 2017). Therefore, issues of data migration and storage are integral to the project as well. Digitalized originals and access copies are distributed geographically, and the original films are housed at the Library of Congress.

The undertaking of positioning the Tribesourcing Southwest Film Project as an interactive, multimedia, multiethnic, and polyvocal resource raises both workaday and theoretical issues, among them the need for Native language presence in the archive as a whole. Informed, intentional practice is essential. Thus, every stage of the project requires consultation and collaboration with our partners in Native Nations. This project seeks to contribute to ongoing efforts to decolonize the archive and restore voice and narrative sovereignty to the people who appear in these films—as agents of their own information rather than subjects of a governmental or corporate agenda. Participation, Equity, and Inclusion are central to this project. This project is supported by a grant from the (U.S.) National Endowment for the Humanities.

References

- Kovach, Margaret. (2010). Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. University of Toronto Press.

- Lawson, Gerry. (2017). “Indigitization: It Takes a Community.” Presentation, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. http://www.digitalassetsymposium.com/2017/06/26/indigitization-it-takes-a-community/

- Posner, Miriam. (2016). “How Is A Digital Project Like a Film?” The Arclight Guidebook to Media History and the Digital Humanities, edited by Charles R. Acland and Eric Hoyt, pp. 184- 194.

- Protocols for American Indian Archival Materials. (2006).

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous People. London: Zed Books.

- Traditional Knowledge (TK) Labels. http://localcontexts.org/tk-labels/