1. Abstract

Purpose

Our final research goal is to restore Edo’s historical city conditions (Tokyo’s former name before the late 19th century) using historical materials. In particular, we focus on non-textual materials. For textual materials, TEI is the de facto standard. For non-textual materials, we need to find new ways as just collecting images is insufficient. We need to organize images as data for analysis across historical materials.

Material and Method

The tool used for this work is the IIIF Curation Platform (ICP)[1]. “Curation” with ICP is a generic method that allows us to gather IIIF images or parts of images and add metadata to each. Curation allows images to be organized as structured and reusable data[2].

A large number of digitized pre-modern Japanese books are being released by multiple Japanese institutions[3]. We used ICP to organize 1255 images from eight guidebooks in the Edo period[4] then organized 2489 images from the Edo shopping guidebook[5].

Findings and Discussion

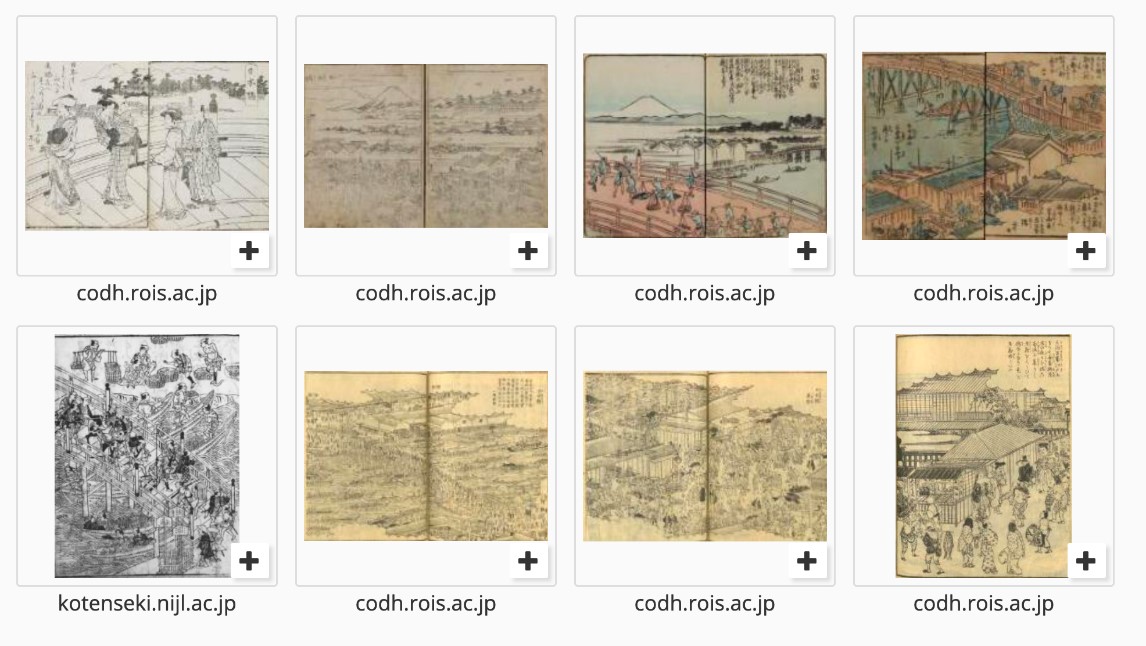

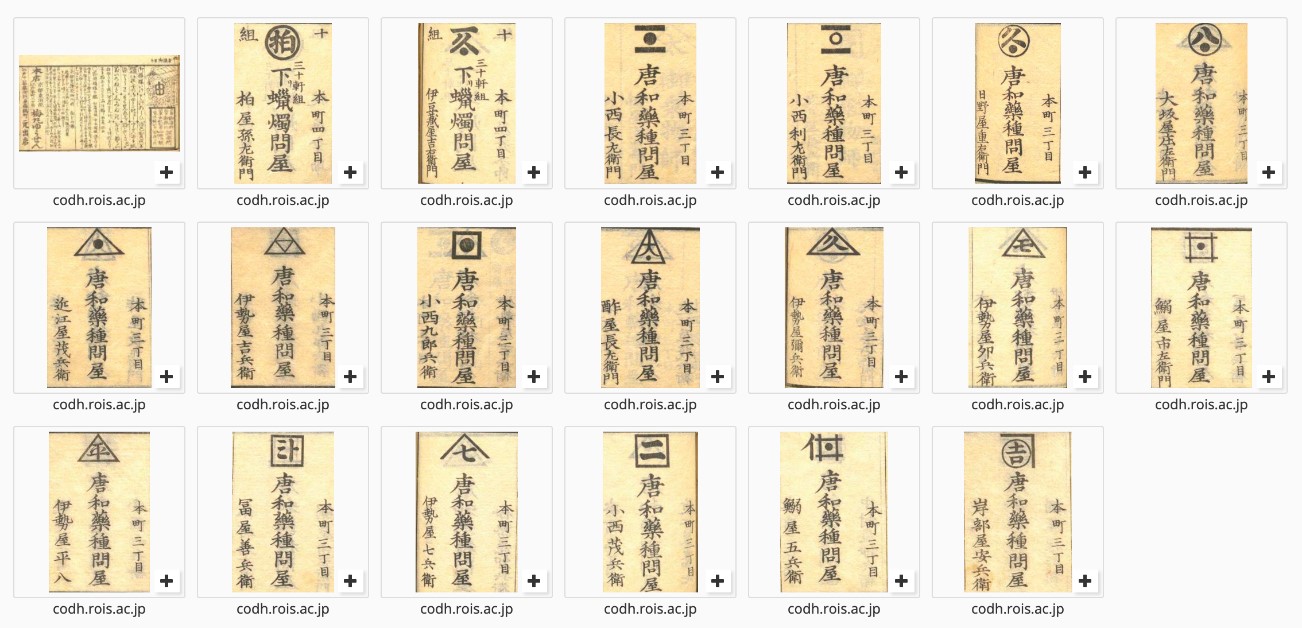

The current curated data confirmed the relationship between famous places and commerce. Presently, our finding reconfirms previous studies[6],[7]. The Asakusa area has many shops around Sensoji Temple today. However, there were many medicine dealers in one corner of Nihonbashi area unlike today (Figure 1–2).

By applying our method to Edo period publications, we not only structure useful information for our research, but also provide reusable data for other researches.

Figure 1: Nihonbashi area illustration curated from Edo guidebooks. Nihonbashi was one of the most famous places in the Edo period.

Figure 1: Nihonbashi area illustration curated from Edo guidebooks. Nihonbashi was one of the most famous places in the Edo period.

Figure 2: Advertisement of Nihonbashi merchant curated from the Edo shopping guidebook . There are many Chinese and Japanese medicine dealers 唐和薬種問屋 unlike today.

Figure 2: Advertisement of Nihonbashi merchant curated from the Edo shopping guidebook . There are many Chinese and Japanese medicine dealers 唐和薬種問屋 unlike today.

References

[1] IIF Curation Platform http://codh.rois.ac.jp/icp/index.html.en

[2] Suzuki, C. Kitamoto, A. (2019). “IIIF Curation Platform ni yoru Edo-Kaimono-Hitori-Annai no microcontents ka”, Jinmonkon2019, pp.11–18

[3] Database of Pre-Modern Japanese Works, https://kotenseki.nijl.ac.jp/?ln=en

[4] Illustration of Edo Famous Places, http://www.ch-suzuki.com/icpedo/finder/?lang=en

Primary sources:

Asai, Ryoi. (1662). Edo-Meisho-Ki , Dataset of Pre-modern Japanese Works, doi: 10.20730/100000011

Kondo, Kiyoharu. (1663). Edo-Meisho-Hyakunin-Isshu, National Diet Library Digital Collection, doi: 10.11501/1183942

Burin, Shoufu. (1795). Ehon-Edo-Zakura, Dataset of Pre-modern Japanese Text, doi: 10.20730/200014989

Shinratei. (1795). Ehon-Edo-No-Mizu, Dataset of Pre-modern Japanese Text, doi: 10.20730/200013678

Saito, Choushu. (1834–1836). Edo-Meisho-Zue, Dataset of Pre-modern Japanese Text, doi: 10.20730/100249896

Utagawa, Hiroshige. (1850–1867) Ehon-Edo-Miyage, Dataset of Pre-modern Japanese Text, doi: 10.20730/200013687

[5] Curation of Merchant in Edo http://www.ch-suzuki.com/edoshop/finder/?lang=en

Primary source:

Nakagawa, Gorozaemon. (1824). Edo-Kaimono-Hitori-Annai, Dataset of Pre-modern Japanese Text, doi: 10.20730/100249503

[6] Ando, Y. (2005). Kankou Toshi Edo no Tanjo, Shinchosha.

[7] Yamamoto, M. (2005). Edo Kenbutsu to Tokyo Kanko, Rinsen Shoten