1. Abstract

1. Introduction

Stage Directions (SD) have been stated as a “particularly underdeveloped topic” (Aston, Savona 1991: 71), even if this seems to be changing (cf. Aebischer 2003; Detken 2009; Dustagheer, Woods 2017; Habscheid et al. 2018). However, there are hardly any quantitative studies of SD so far (except of Sperantov 1998 who analysed Russian tragedies).

Usually, dramas consist of two types of text: Spoken Text (ST) and SD, where SD often consist of rather formal instructions. To complement existing quantitative approaches to drama, we will profile SD as an object of research in digital literary studies. To this purpose, we will give an exploratory analysis of quantitative features of SD using 384 German plays. Subsequently, we will characterise the development of SD over a period of 200 years, using the hypothesis of a “tendency towards epification“ (“Episierungstendenz“, Szondi 1956) as an interpretative framework.

2. Corpus and Workflow

Our corpus is based on the drama collection GerDraCor (Fischer et al. 2019). Even though literary studies has not yet reached a consensus on a definition of SD (Dustagheer, Woods 2017: 1–16), there are relatively uncontroversial (typographical) conventions what should be regarded as SD (Tonger-Erk 2018: 431–434). Digital editions using TEI (including GerDraCor) encode SD using the

Of the 474 plays available in GerDraCor, we removed librettos and 3 plays without SD, which yields a corpus of 384 plays that are pre-processed using the DramaNLP package1. The package employs the Stanford PoS tagger (Toutanova et al. 2003; STTS tagset: Schiller et al. 1999) and mate lemmatizer (Björkelund et al., 2000) separately on the text types ST and SD. The resulting data is analysed with the DramaAnalysis R package (Reiter 2019).

3. Exploratory Data Analysis

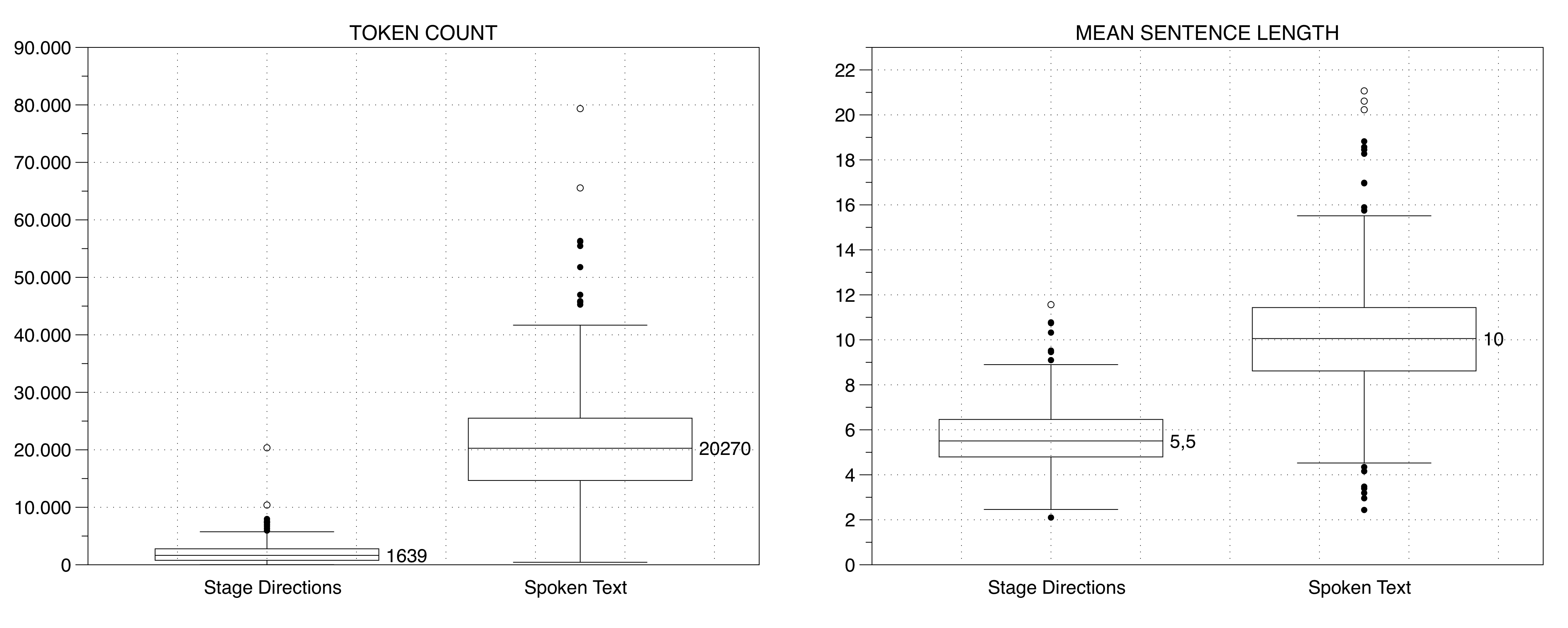

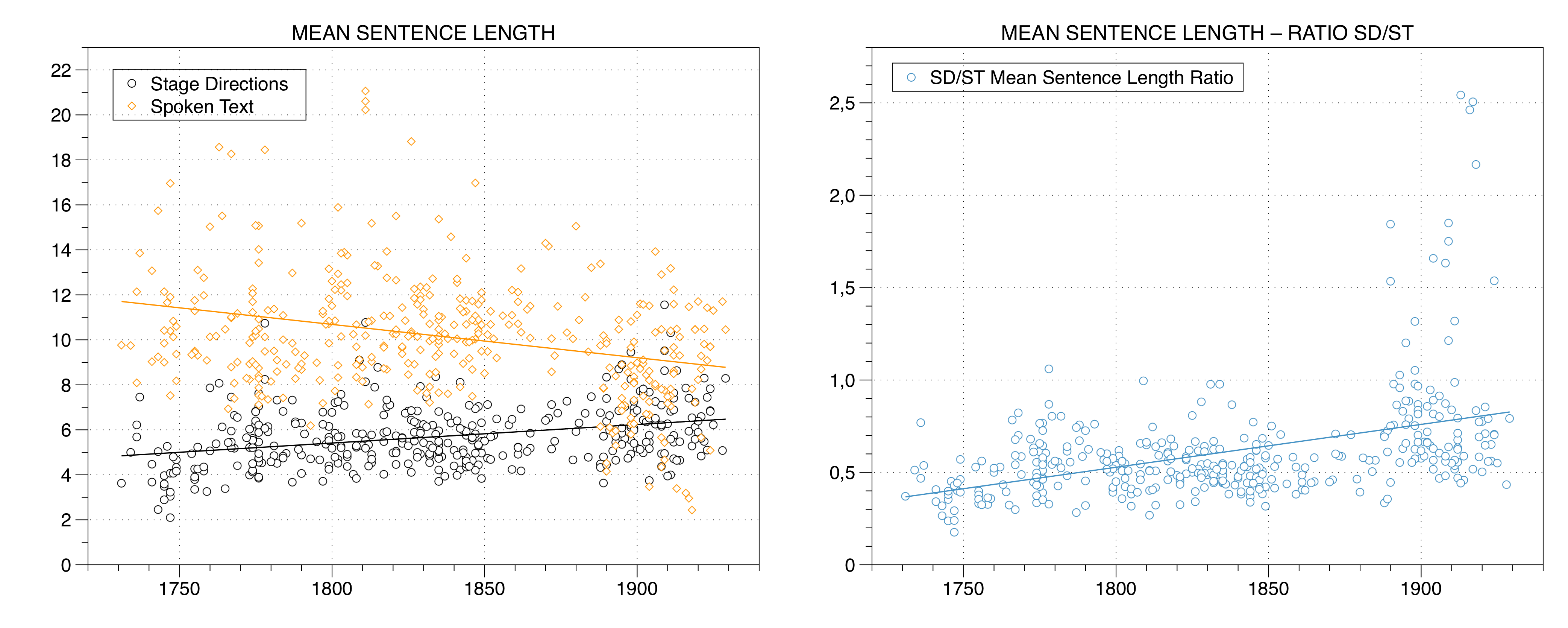

The median number of tokens is 1.639 in SD and 20.270 in ST (Fig. 01), so on average SD takes up 7.48% of the entire text. Additionally, sentences in SD are on average only about half as long as in ST.

Figure 1: Distribution of token count and mean sentence length

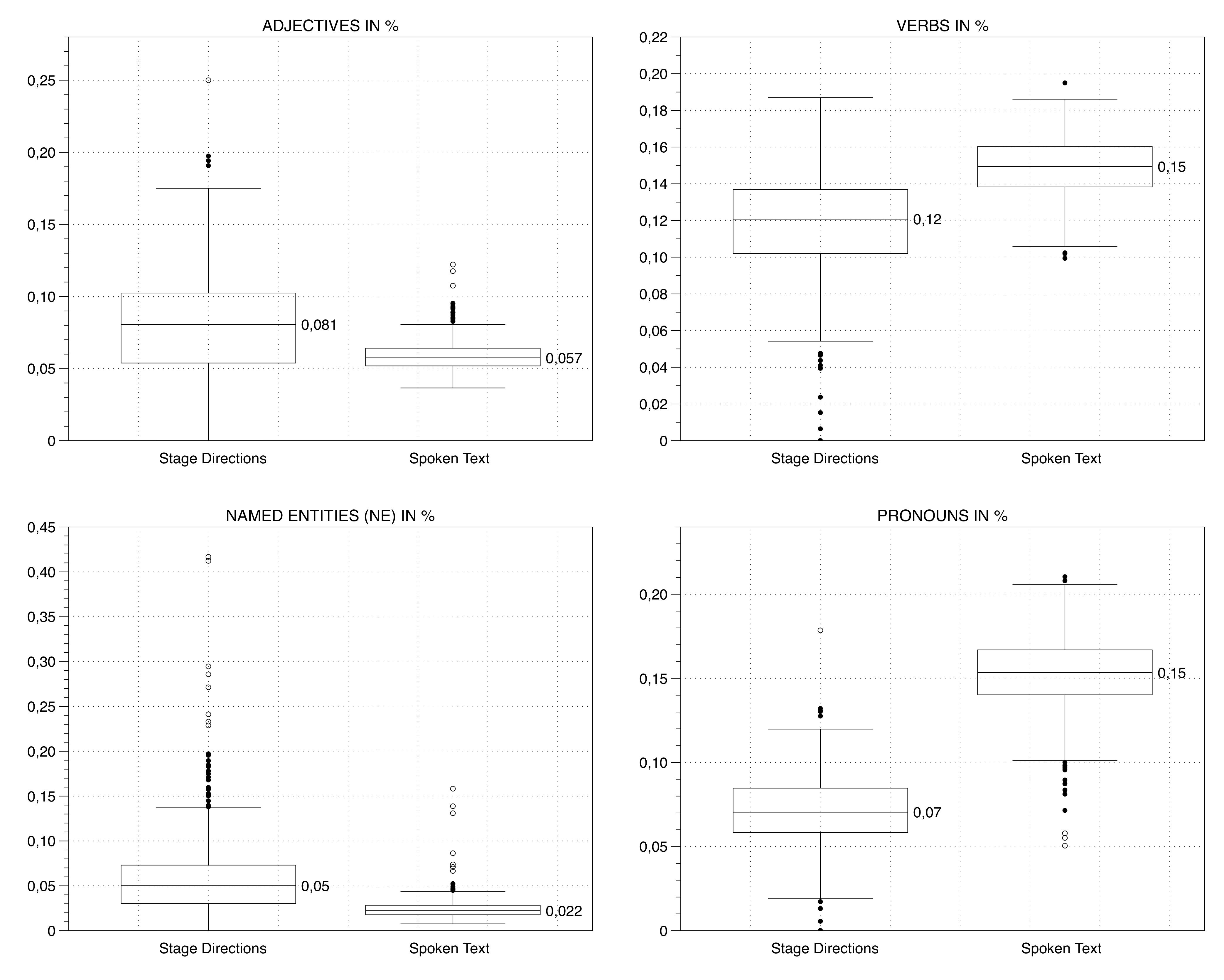

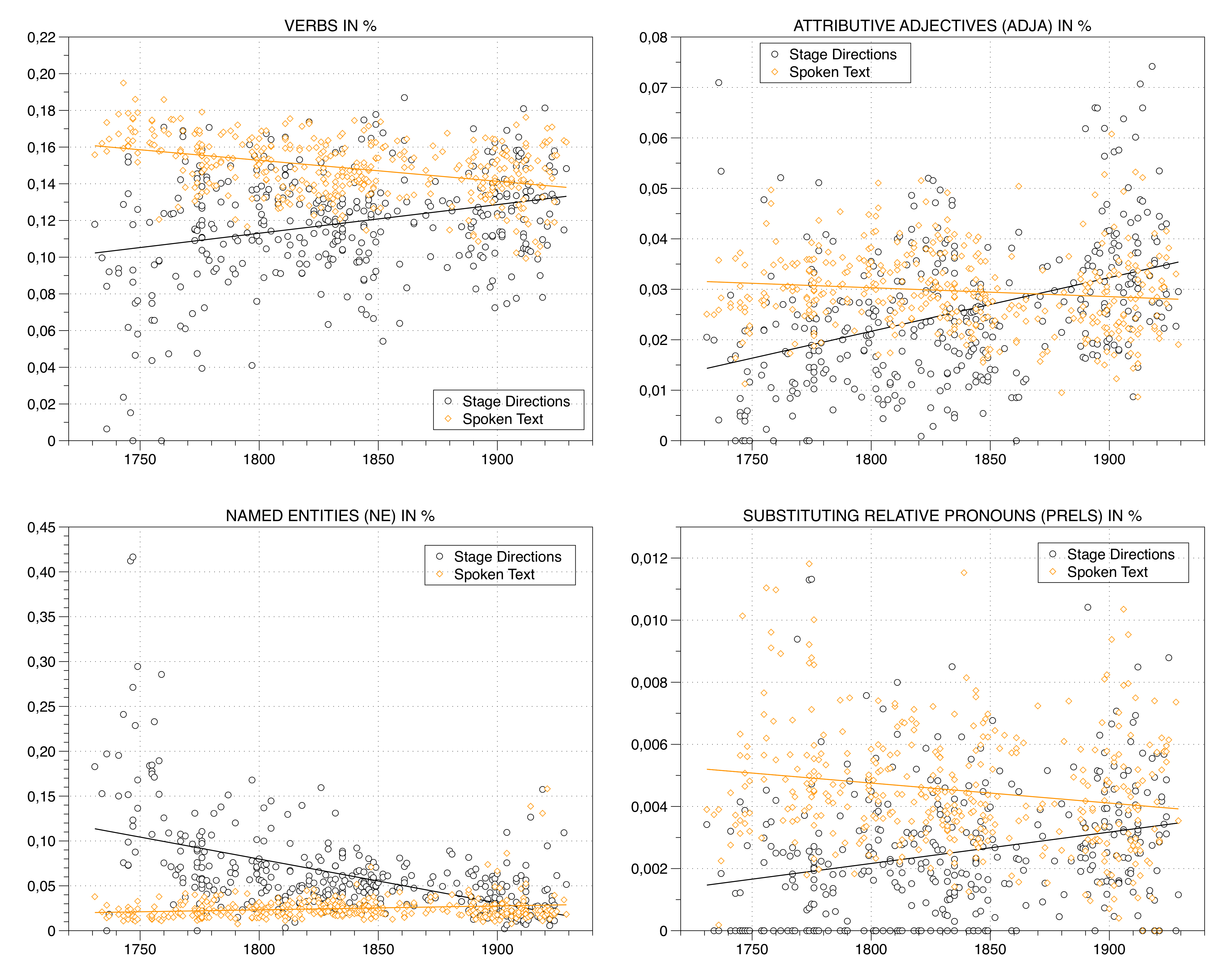

SD and ST also differ in the proportions of certain parts of speech (POS). While SD has a higher percentage of adjectives and named entities, ST has a higher percentage of verbs and pronouns (Fig. 02).

Figure 2: Portion of selected POS2

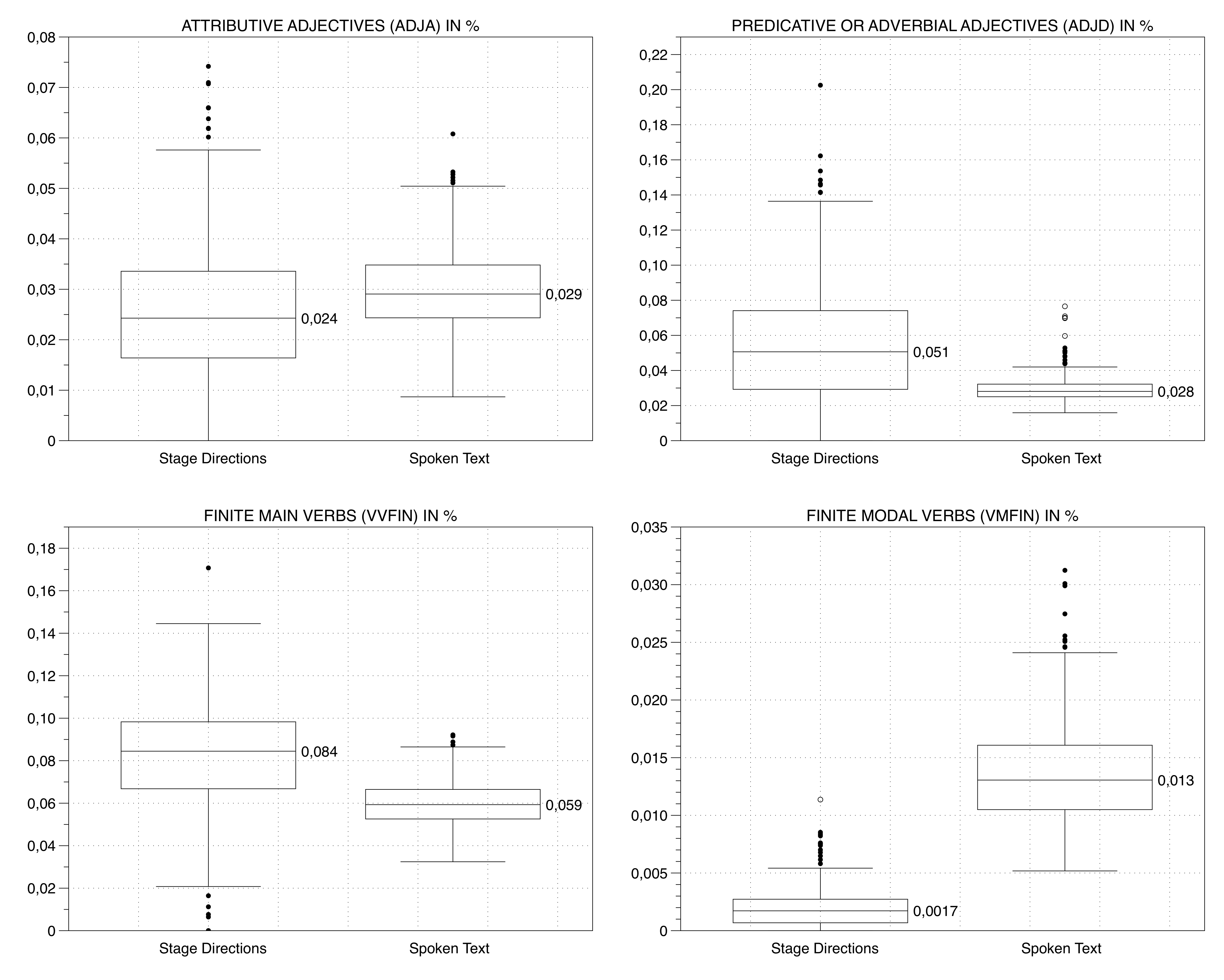

A closer look can be taken by differentiating fine-grained POS tags of adjectives and verbs (Fig. 03). Compared to ST, SD are about named entities (NE) doing something (VVFIN) in a specific way (ADJD), while they lack the rhetorics of addressing (PRO) and modality (VMFIN), which are more characteristic for ST.

Fig. 03: Portion of selected fine-grained POS

4. Epification

While an intense discussion about (Brechtian) "Epic Theater" emerges in the aftermath of the ‘crisis of drama’ around 1890, “epification” in recent narratological and semiotical studies is conceptualised as a specific "mediation of the representation of events by a narrator-like instance" (cf. Weber 2017: 209). In contrast to the SD of 'classical' drama, primarily functioning as an “instruction” (Issacaroff 1988), the epified SD “seems to be incorporating qualities of the novel and the plastic arts” (Suchy 1991:80).

Consequently, we characterise the development of SD in our corpus with respect to such an understanding of epification, with five concrete indicators:

- the proportion of SD in the total text increases, giving more 'word space' to a potential narrative voice;

- sentences in SD get longer, thus becoming similar to SP;

- SD and ST converge in their POS distributions, so that SD approaches ST in the 'verbal gesture‘;

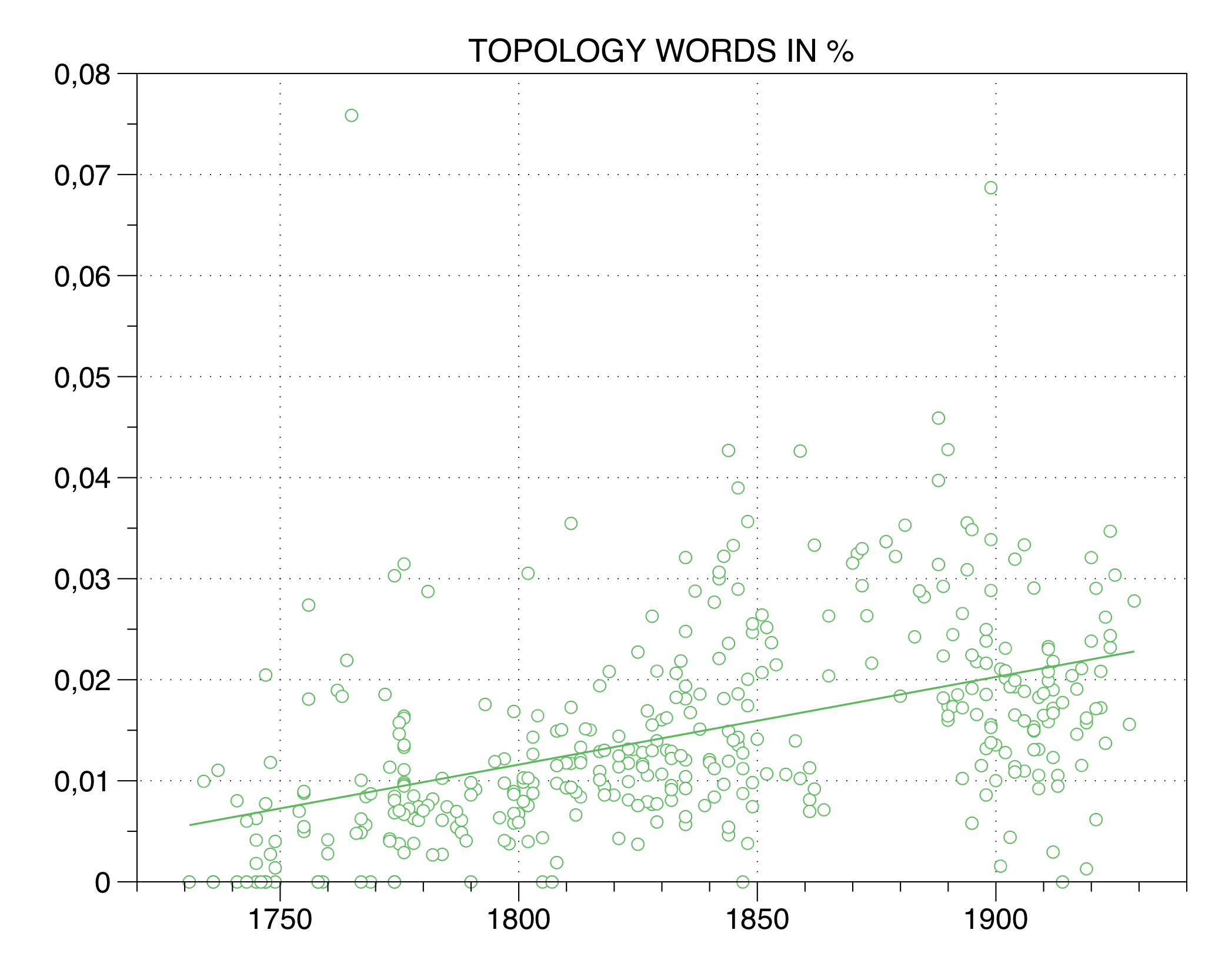

- words describing a location increase in SD, indicating a more concrete shaping of the diegetic world by a narrative voice;

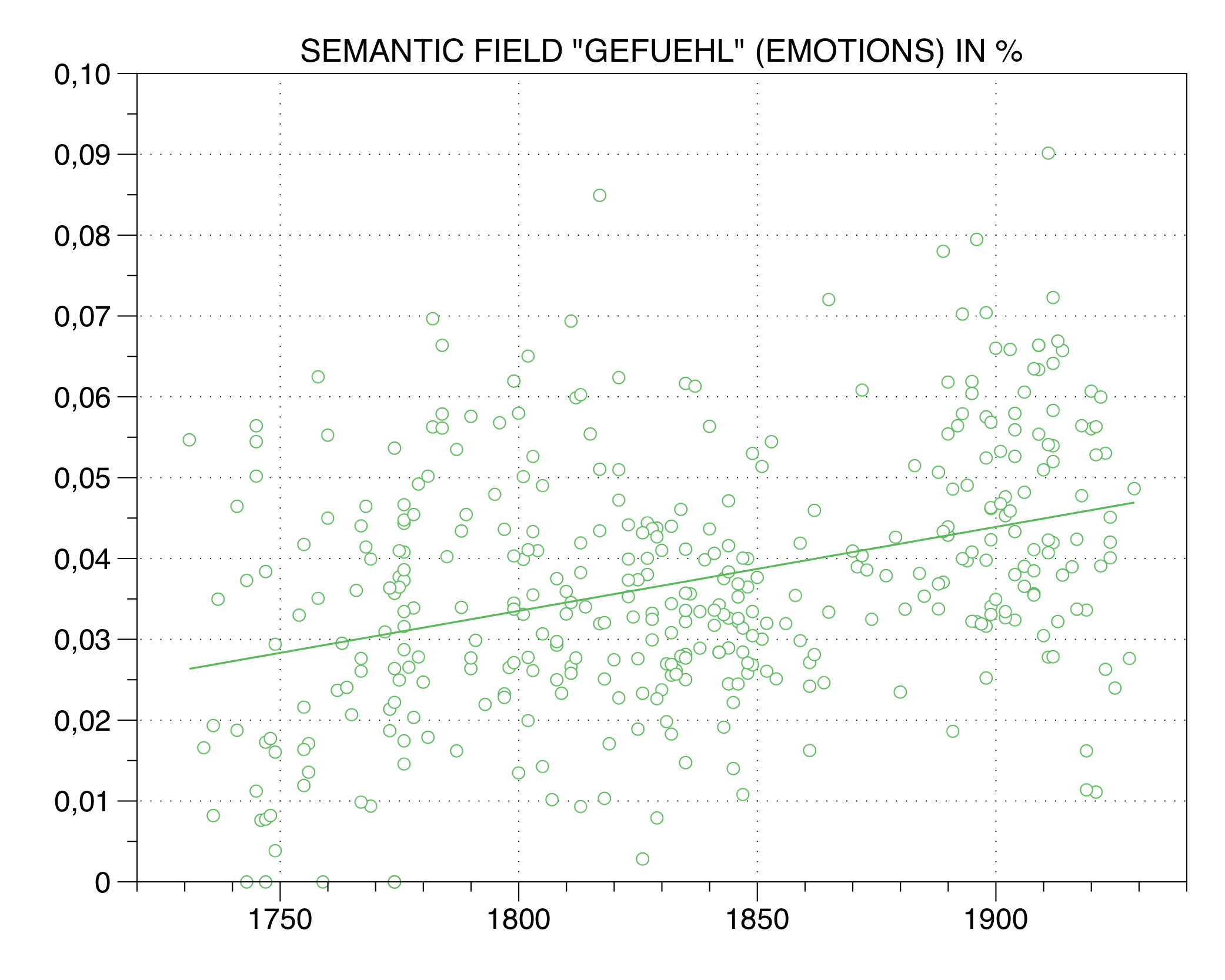

SD becomes more emotional, indicating an increase in evaluations and (possible) internal focalisations, both understood as privileges of the narrator's voice.

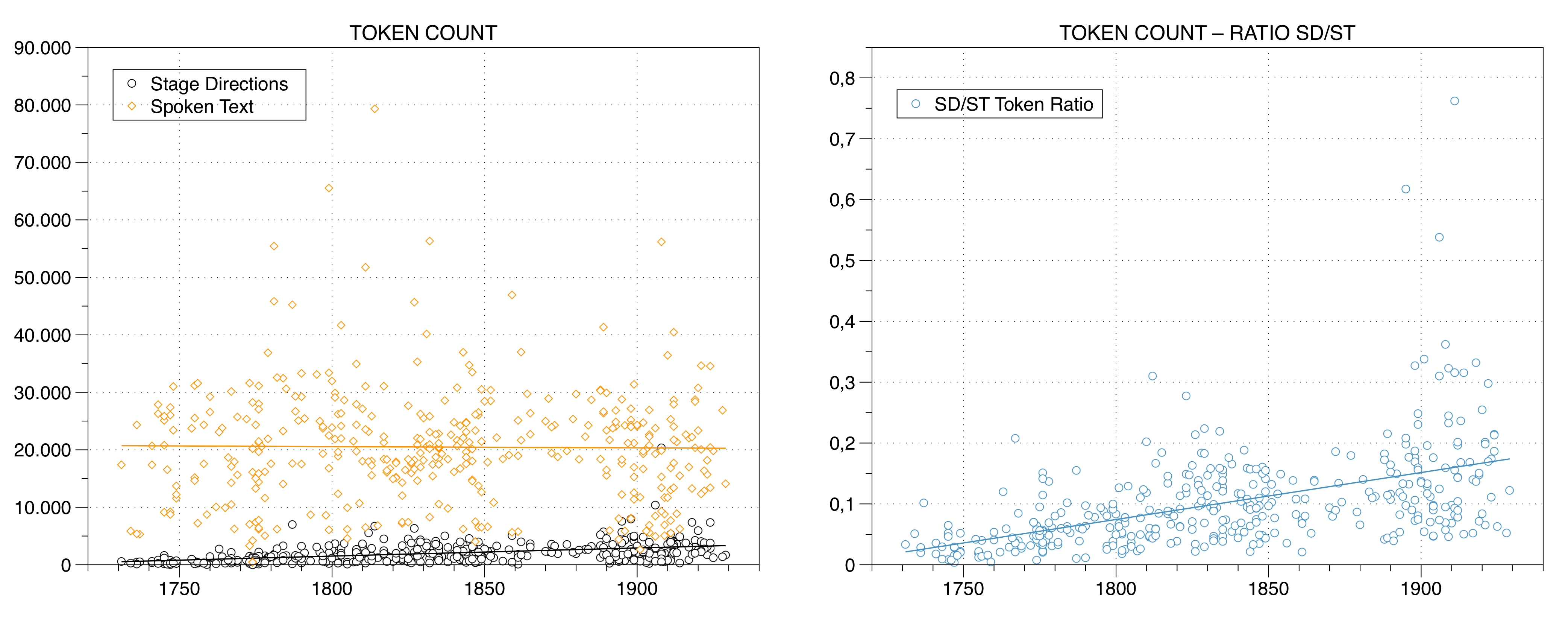

While there is almost no change in the number of tokens in ST, their number in SD increases over time, leading to a substantial increase in the SD/ST ratio (Fig. 04). The same holds for the mean sentence length in SD, which in several dramas 'around 1900' even considerably exceeds the mean sentence length in ST (i.e. ratio over one; Fig. 05).

Figure 04: Historical distribution of token count

Figure 05: Historical distribution of mean sentence length

While verbs (Fig. 02) and attributive adjectives (Fig. 03) are synchronously more frequently found in ST, historically differentiated data shows a convergence of the percentages in SD and ST (Fig. 06). Conversely, the proportion of named entities in SD decreases (Fig. 06). Also noteworthy is the convergence of the proportion of relative pronouns in SD and ST (Fig. 06), which suggests an increase in sentence complexity in SD. Overall, SD and ST become more similar over time.

Figure 06: Historical distribution for selected POS

In order to explore 'topologisation', we defined a lexicon of topological terms. 3 As Fig. 07 shows, a considerable increase in topological words in SD can be observed, which can be interpreted as a more concrete topological order of the diegesis on the stage.

Figure 07: Historical distribution for topological words

Finally, using word-related information from GermaNet 11 (Hamp/Feldweg 1997), we calculated the percentage of words (adjectives, nouns, verbs) from the semantic field 'GEFUEHL' (emotions). As Fig. 08 shows, there is also a clear increase in such words in SD.

Figure 08: Historical distribution for ‘emotion‘ words

5. Conclusion

Our examinations outlined SD as a relevant object of research for a quantitative history of drama. We demonstrated that SD is a text layer that differs from ST in several aspects. By examining the historical development of SD, we have shown a transformation of SD between 1730 and 1930, which we linked back to the “tendency towards epification“ in German drama. Further research should develop more complex linguistic operationalisations of epification, and be extended to plays in other languages.

Bibliography

Pascale Aebischer (2003). Didascalia and Speech in the Dramatic Text. In: Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism 17.2 (2003), pp. 25–44.

Elaine Aston, George Savona (1991). Theatre as Sign System. A Semiotics of Text and Performance. London, New York: Routledge.

Anders Björkelund, Bernd Bohnet, Love Hafdell,Pierre Nugues (2010). A high-performance syntactic and semantic dependency parser. In: Coling 2010: Demonstrations, pp. 33–36, Beijing, China, August 2010. Coling 2010 Organizing Committee. URL: http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/C10-3009.

Anke Detken (2009). Im Nebenraum des Textes Regiebemerkungen in Dramen des 18. Jahrhunderts. Tübingen: Niemeyer 2009.

Sarah Dustagheer, Gillian Woods (eds.) (2017). Stage Directions and Shakespearean Theatre. Bloomsbury: London, New York.

Frank Fischer, Ingo Börner, Mathias Göbel, Angelika Hechtl, Christopher Kittel, Carsten Milling, Peer Trilcke (2019). Programmable Corpora: Introducing DraCor, an Infrastructure for the Research on European Drama. In: Proceedings of DH2019: "Complexities". Utrecht. URL: https://dev.clariah.nl/files/dh2019/boa/0268.html.

Stephan Habscheid, Constanze Spiess, Hartmut Bleumer, Niels Werber (eds.) (2018). Hauptsache Nebentext. Regiebemerkungen im Drama. LiLi – Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik. Vol. 48, no. 3 (September 2018). Metzler, Stuttgart 2018.

Birgit Hamp, Helmut Feldweg (1997). GermaNet-a Lexical-Semantic Net for German. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Automatic Information Extraction and Building of Lexical Semantic Resources for NLP Applications on the conference of the Association of Computational Linguistics (ACL), 1997.

Michael Issacaroff (1988). Stage Codes. In: Performing Texts, ed. Michael Issacharoff, Robin F. Jones. U of Pennsylvania P, Philadelphia, pp. 59-74.

Nils Reiter (2019). DramaAnalysis 3.0.0. Available in CRAN. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3250613.

Anne Schiller, Simone Teufel, Christine Stöckert, Christine Thielen (1999). Guidelines für das Tagging deutscher Textcorpora mit STTS. Annotation guidelines. URL: http://www.sfs.uni-tuebingen.de/resources/stts-1999.pdf.

V. V. Sperantov (1998). Poetika remarki v russkoy tragedii XVIII – nachala XIX vv. (K tipologii literaturnykh napravleniy) [The Poetics of Stage Directions in Russian Tragedy of the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries (On the Typology of Literary Movements)]. In: Philologica, vol. 5, no. 11/13 (1998), pp. 9–48. URL: https://rvb.ru/philologica/05/05sperantov.htm.

Patricia A. Suchy (1991). When Words Collide: The Stage Direction as Utterance. In: Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism 6.1 (1991), pp. 69–82.

Peter Szondi (1956). Theorie des modernen Dramas. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt.

Lily Tonger-Erk (2018). Das Drama als intermedialer Text. Eine systematische Skizze zur Funktion des Nebentextes. In LiLi – Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik. Vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 421–444.

Kristina Toutanova, Dan Klein, Christopher Manning, Yoram Singer (2003). Feature-Rich Part-of-Speech Tagging with a Cyclic Dependency Network. In: Proceedings of HLT-NAACL, pp. 252–259.

Alexander Weber (2017). Episierung im Drama. Ein Beitrag zur transgenerischen Narratologie. De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston.

Notes

1 https://github.com/quadrama/DramaNLP; doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3451307

2 “ADJECTIVE” = ADJA, ADJD; “VERB” = VAFIN, VAIMP, VAINF, VAPP, VMFIN, VMINF, VMPP, VVFIN, VVIMP, VVINF, VVIZU, VVPP; “PRONOUNS” = PDAT, PDS, PIAT, PIDAT, PIS, PPER, PPOSAT, PPOSS, PRELAT, PRELS, PRF.