1. Abstract

Introduction

Digital paleography has been emerging as a field of research since the beginning

of the new century. Paleographers, describe how a text has been displayed, and

collect information such as writing styles, contextual information and the epoch.

Ciula (2017) gives a good summary about digital paleography and its practices.

Challenges concerning digital paleography are discussed by Hassner et al. (2015)

for writing systems and discussed more broadly in Stokes (2015). The main

results of these publications is, that the community of digital paleographers,

which was mainly focused on a few particular languages, sees to broaden its

scope and to research more global models to represent paleographic features

such as writing style, typographic features and anomalies in texts. This calls for

a unified representation of paleographic features to which this publication would

like to contribute by suggesting a core vocabulary for paleographic description

of texts.

Related Work

Paleographic features can to a certain extent be represented in TEI/XML1 Wit-tern et al. (2009) (scribal shifts, scribal alterations) as highlighting annotations.

For systematic non-alphabetic languages, encodings can be developed to repre-

sent the shape of the characters, e.g. for cuneiform and egyptian hieroglyphics

Homburg (2019), van den Berg (1997)

In the linguistic community, linguistic linked open data (LLOD)McCrae et al.

(2016) is very present and allows for tools such as BabelNet Navigli & Ponzetto

(2012), a multilingual semantic network to translate words and texts based on

semantic content. This publication suggests to create such a semantic network

for paleographic descriptions in order to formalize this part of research. Natu-

rally, such a task cannot be done by a single scholar from a single field, so the

publication begins by suggesting vocabulary contents documenting the structure

of systematic scripts like cuneiform and to model relations between components

of parts of scripts, the so-called core vocabulary. Especially structured scripts

(cf. fig. 1) expose a variety of encoding schemes for e.g. Chinese Bishop & Cook

(2003), Japanese Apel (2014). Those encodings have been created to model

fonts, but form an ideal basis to create the proposed unified vocabulary. Similar

to the OliA ontologies Chiarcos & Sukhareva (2015) the author suggests to ex-

tend this core vocabulary representing the structure of the script (figure 3) by

language/script specific extensions. The concept will be presented using the ex-

ample of cuneiform and egyptian hieroglyphics and builds upon the vocabulary

shown in figure 2.

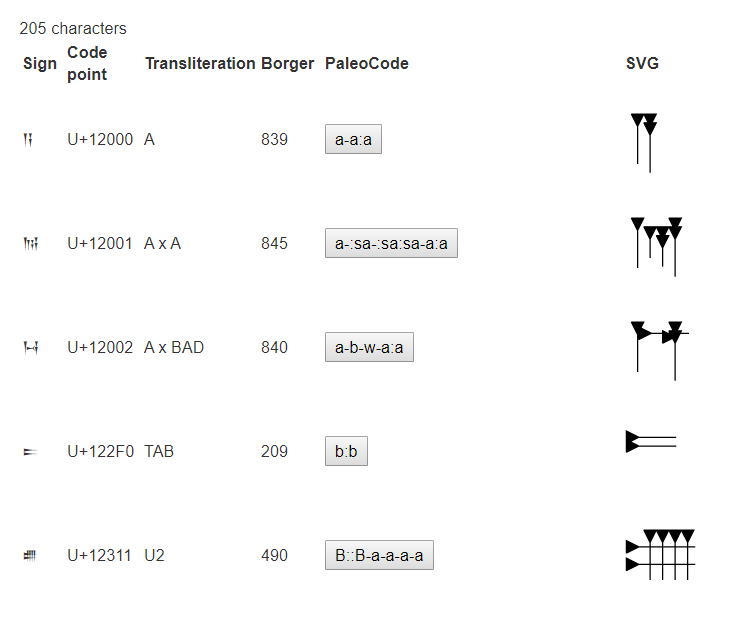

Figure 1. Example of the PaleoCodage encodingHomburg (2019): PaleoCodage repre-

Figure 1. Example of the PaleoCodage encodingHomburg (2019): PaleoCodage repre-

sents a machine-readable way to describe highly structured scripts such as cuneiform.

This structure, relations to other similar characters and scripts can be modelled using

the proposed core vocabulary, while the language specific vocabularies would describe

writing styles, shapes and stilistic characteristics of the respective script.

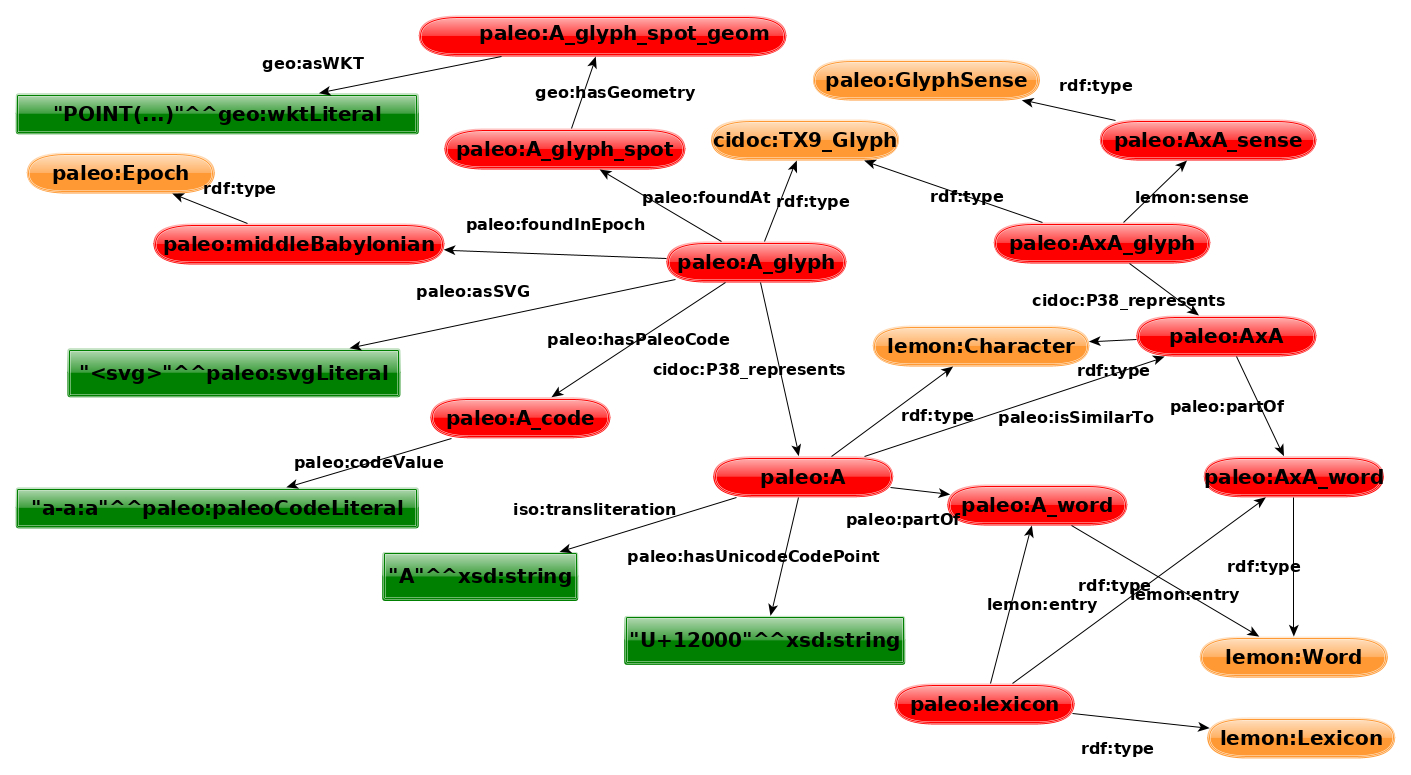

Figure 2: Vocabulary describing two cuneiform glyphs connected to character rep-

Figure 2: Vocabulary describing two cuneiform glyphs connected to character rep-

resentations, their finding spot, their assigned epoch, an assigned glyph sense (which

may be distinct from the character/word sense) and possible serializations in SVG and

as a PaleoCode. For other languages other encodings are possible.

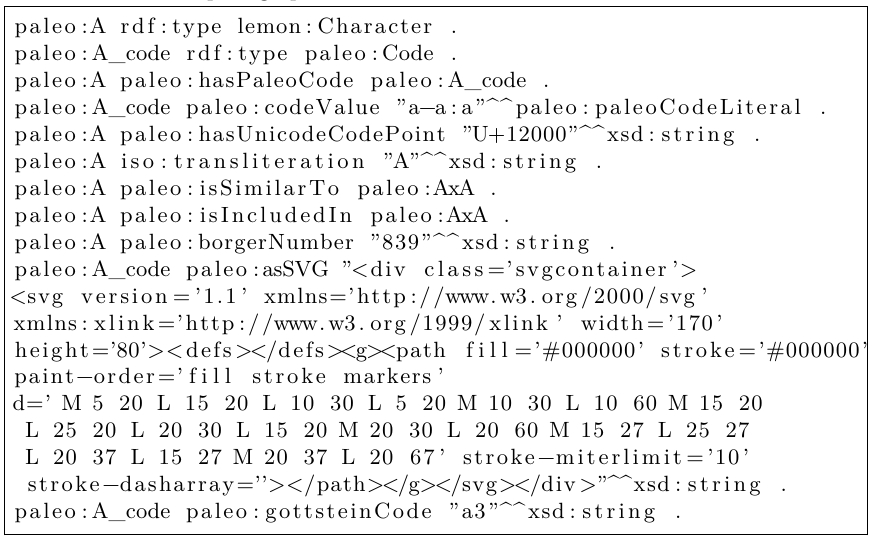

Figure 3: Excerpt: PaleoCodage Vocabulary describing a cuneiform sign. The

Figure 3: Excerpt: PaleoCodage Vocabulary describing a cuneiform sign. The

sign’s structure is described using a PaleoCode which could itself be described using

Semantic relations. These relations allow to model the structure of script subelements

with extensions for paleographic features

Bibliography

Apel, U. (2014), ‘Kanjivg’, kanji SVG dataset, Creative Commons BY-SA 3. 3Bishop, T. & Cook, R. (2003), A specification for cdl character description

language, in ‘Glyph and Typesetting Workshop’. 3

Chiarcos, C. & Sukhareva, M. (2015), ‘Olia–ontologies of linguistic annotation’,

Semantic Web 6(4), 379–386. 3

Ciula, A. (2017), ‘Digital palaeography: What is digital about it?’, Digital Schol-

arship in the Humanities 32(suppl_2), ii89–ii105. 1

Hassner, T., Rehbein, M., Stokes, P. A. & Wolf, L. (2015), ‘Computation and

palaeography: potentials and limits’, Kodikologie und Paläographie im Dig-

italen Zeitalter 3: Codicology and Palaeography in the Digital Age 3 p. 1.

1

Homburg, T. (2019), Paleo codage - a machine-readable way to describe

cuneiform characters paleographically, Utrecht, Netherlands.

URL: https://dev.clariah.nl/files/dh2019/boa/0259.html 2, 1

McCrae, J. P., Chiarcos, C., Bond, F., Cimiano, P., Declerck, T., De Melo,

G., Gracia, J., Hellmann, S., Klimek, B., Moran, S. et al. (2016), The open

linguistics working group: developing the linguistic linked open data cloud,

in ‘Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources

and Evaluation (LREC 2016)’, pp. 2435–2441. 3

Navigli, R. & Ponzetto, S. P. (2012), ‘Babelnet: The automatic construction,

evaluation and application of a wide-coverage multilingual semantic network’,

Artificial Intelligence 193, 217–250. 3

Stokes, P. A. (2015), ‘Digital approaches to paleography and book history: some

challenges, present and future’, Frontiers in Digital Humanities 2, 5. 1

van den Berg, H. (1997), ‘Manuel de codage: A standard system for the

computer-encoding of egyptian transliteration and hieroglyphic texts’, Centre

for Computer-Aided Egyptological Research (CCER) . 2

Wittern, C., Ciula, A. & Tuohy, C. (2009), ‘The making of tei p5’, Literary and

Linguistic Computing 24(3), 281–296. 2

This presentation presents first efforts to develop a vocabulary for paleographic features across different languages. It will feature a case study using cuneiform languages to infer relevant elements for a general vocabulary for paleography. The poster can be seen as a point of discussion and invitation for colleagues of similar and other fields to further develop the vocabulary which can be used to describe writing styles. When finished it is planned to be used among others to benefit machine learning tasks in computational lingustics as a paleographic desctiption of signs can act as a source of features which is rarely exploited in such scenarios.