1. Abstract

Historical documents often undergo transformations–transcription, annotation, re-formatting, and digitization–as part of preservation or humanistic inquiry. These processes modify documents’ content, artifactual form, and structure, which subsequently influences the ways in which they are read, explored, and interpreted. Transparency of such processes ensures proper attribution of curators’ labor, promotes greater inclusiveness, and enables a more holistic and critical interpretation of historical records. But how to engage with and make visible these transformation processes? In this paper, we begin to address this question through a visualization case study based on an exemplary collection of biographical student records from the University of St Andrews (Scotland) that date back to the 18th century. We present – illustrated through this case study - a methodology based on visual (re)-interpretations of historical records over time which, we believe, is relevant to a wide range of information collections within and beyond humanities research.

Biographical Student Records

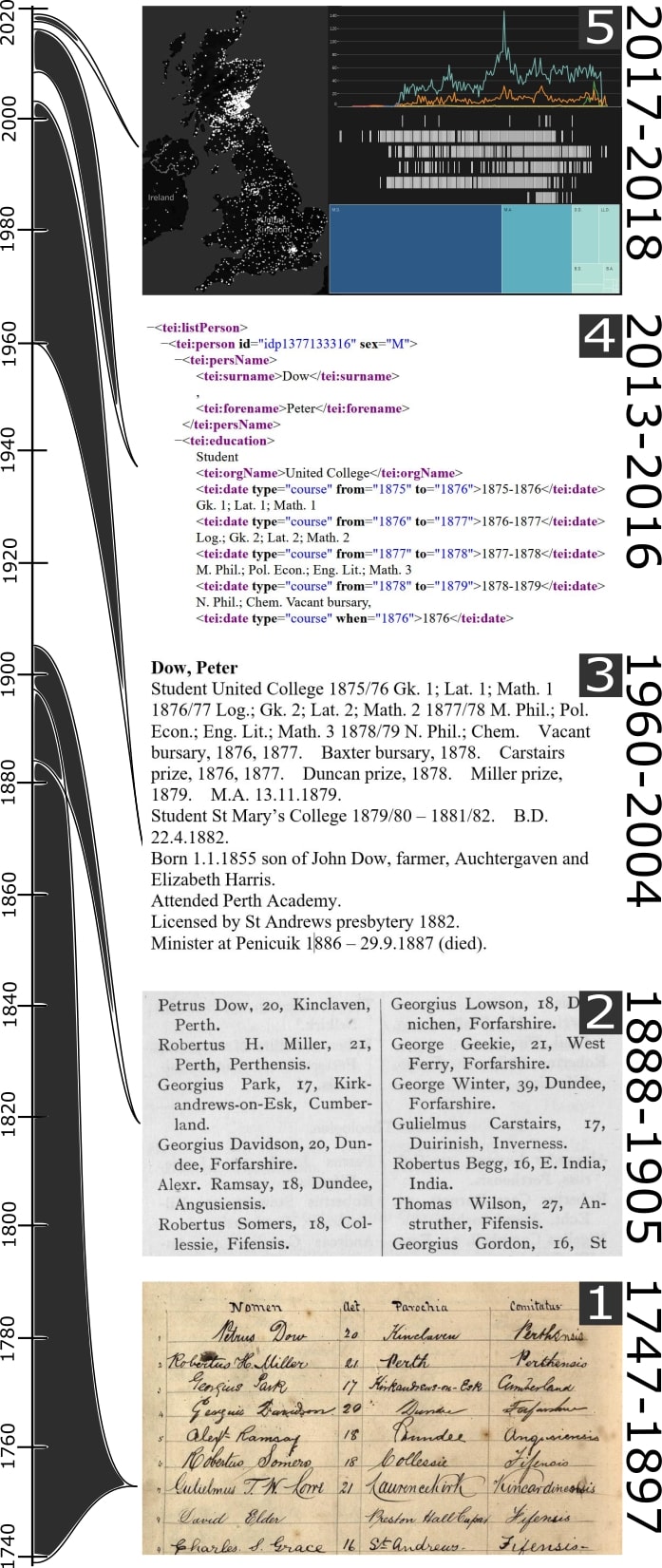

The handwritten student records (1747-1897) collected by the University of St Andrews originally included students’ name, age, church affiliation and birthplace (Fig. 1.1), but over the course of two centuries, they have undergone a variety of transformations (Fig. 1). From 1888 to 1905 the records were transcribed by the University archivist, James Maitland-Anderson (Maitland Anderson, 1905; Fig. 1.2). Between 1960 and 2004, one of Maitland-Anderson’s successors, Dr Robert Smart, revised these transcriptions and expanded the records with students’ parental lineage, courses taken, and floruit, drawing from a large variety of sources (Smart, 2004; Fig. 1.3). From 2013 to 2016, a team around Dr Alice Crawford from the University library transformed Smart’s work into machine-readable form using Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) (Fig. 1.4) which resulted in a web interface that allows targeted searches. In 2017, we transformed the data from Crawford’s work into a relational database which enabled the visualization of the records’ content (Vancisin et al., 2018; Fig. 1.5). To better understand the nature and impact of such modifications, we conducted interviews with the archivists, historians, and software engineers who have worked on these transformations. In combination with researching previous work on the records (Maitland Anderson, 1905; Smart, 2004), these interviews helped us identify and characterize four key transformations the records have undergone.

Figure 1: Records' Transformations.

Figure 1: Records' Transformations.

Transcription. Maitland-Anderson and Smart transcribed the original handwritten documents into print form. This process required expertise in paleography and entailed interpretations, for example, of name spellings (e.g., Maitland-Anderson preserved the Latin ‘Petrus’ Dow; while Smart changed it to ‘Peter’; Fig. 1.1-1.3).

Expansion. The records have been expanded by adding information from other archives (Smart), linking records to students’ publications (Crawford), and geo-encoding location mentions

(Vancisin). These expansions can be considered as interpretations, informed by third-party sources.

Re-Structuring. Maitland-Anderson deliberately preserved the structure of the original records, while Smart transformed them into an alphabetical index, enabling searches by-name but irrevocably removing the records’ temporal order. Crawford’s tagging imposed a rigid content structure on each record. Our database reconfigures and stores key information (dates, places etc.) in separate but linked tables. This re-structuring allowed new ways of representing and exploring the records, but also introduced additional interpretation layers.

Artifactual Form. Transforming the handwritten records into print enabled easy record parsing, while the structural transformations allowed for new visual and textual representations and interactions. However, the individual human imprint of the handwritten text is lost in these transformations and so are their materiality and visual aesthetics (Forlini et al., 2018). These transformation processes can be considered as re-interpretations of the original records that enable new ways of engagement and representation. However, the fact that the records’ transformations are typically invisible is problematic from an ethical (Correll, 2019) and research perspective, because how we represent information fundamentally shapes our interpretation and the questions we ask. Moreover, an unawareness of underlying transformations hampers the holistic interpretation of historical records.

Visualization Opportunities

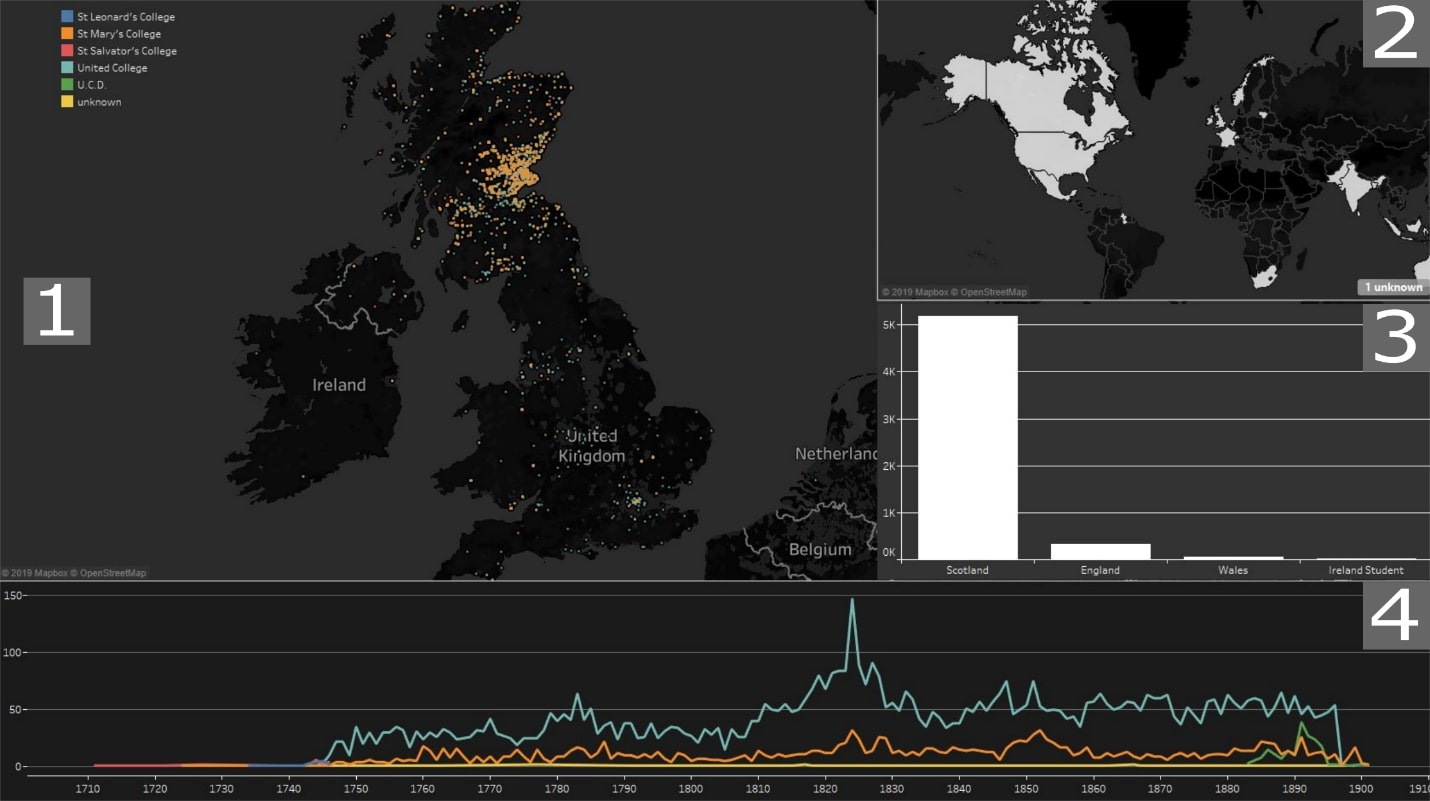

Historical document visualization mainly focuses on providing access to the content of the collection in its ‘final’ stage (i.e., Edelstein et al., 2017; Hinrichs et al., 2015; Hyvönen et al., 2017), and our previous work is no exception (Vancisin, 2018; Fig. 2). Work by Hullman & Diakopulos (2011), however, shifts attention to the importance of weaving information about data provenance into visualization. Wrisley (2018) has promoted the idea of Pre-Visualization which argues for visualization prefaces that provide such perspectives in textual form. Péoux & Houllier (2017) introduce a diagrammatic approach to disclose transformation processes. However, visualization-driven approaches that highlight transformation processes and introduce critical and ethical perspectives to the document collection, its metadata, and their visual representations (Correll, 2019, Dörk et al. 2013, D’Ignazio & Klein, 2016) are unexplored. We have started addressing this challenge by investigating how we can portray the records’ transformation stages through visualization. Our visualization case study shown in Figure 3 presents one example of how this can be achieved.

Figure 2: Visualization of the records' content. (1,2) students' birth places within and outside of the UK; (3) distributions of nationalities; (4) student numbers in different colleges over time.

Figure 2: Visualization of the records' content. (1,2) students' birth places within and outside of the UK; (3) distributions of nationalities; (4) student numbers in different colleges over time.

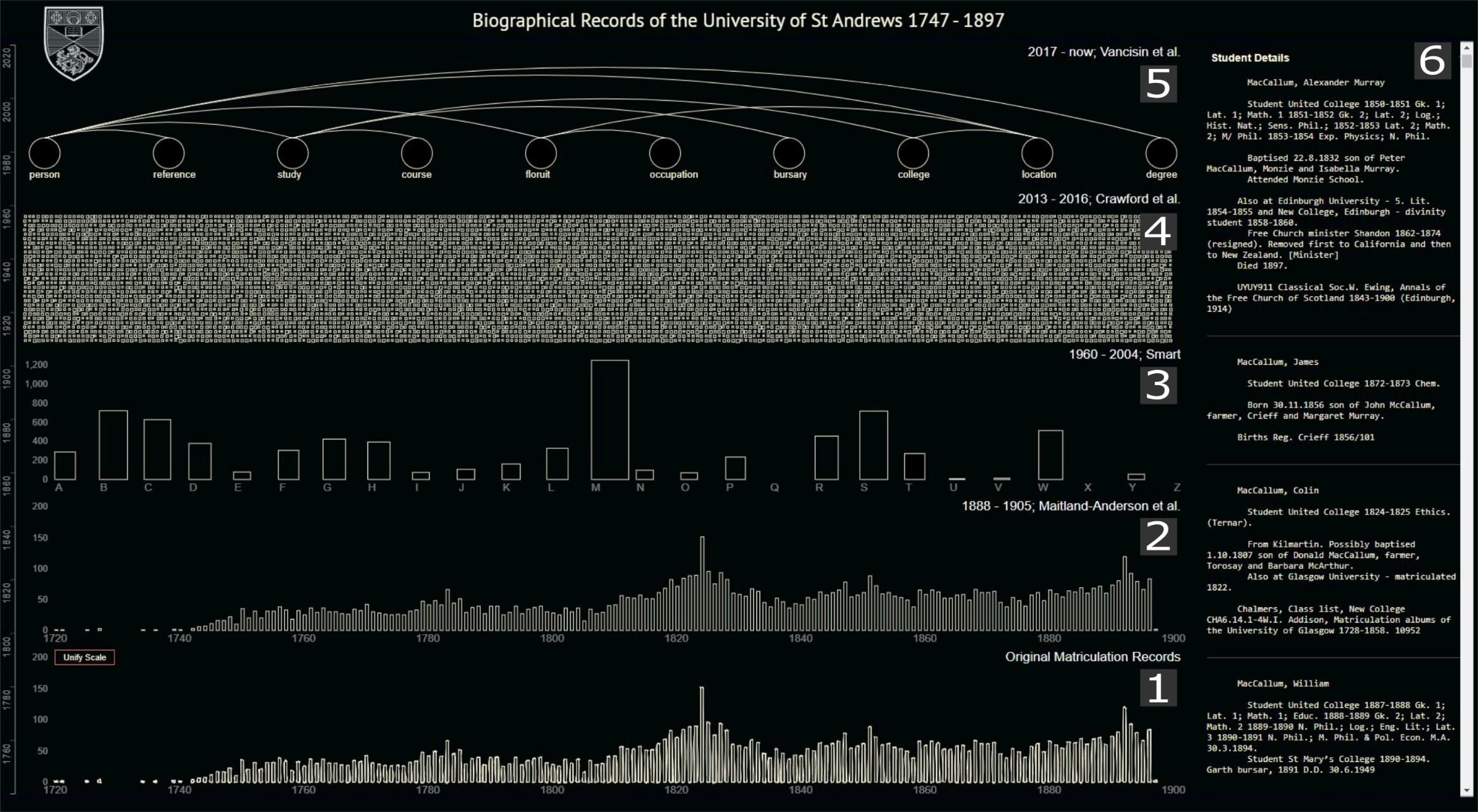

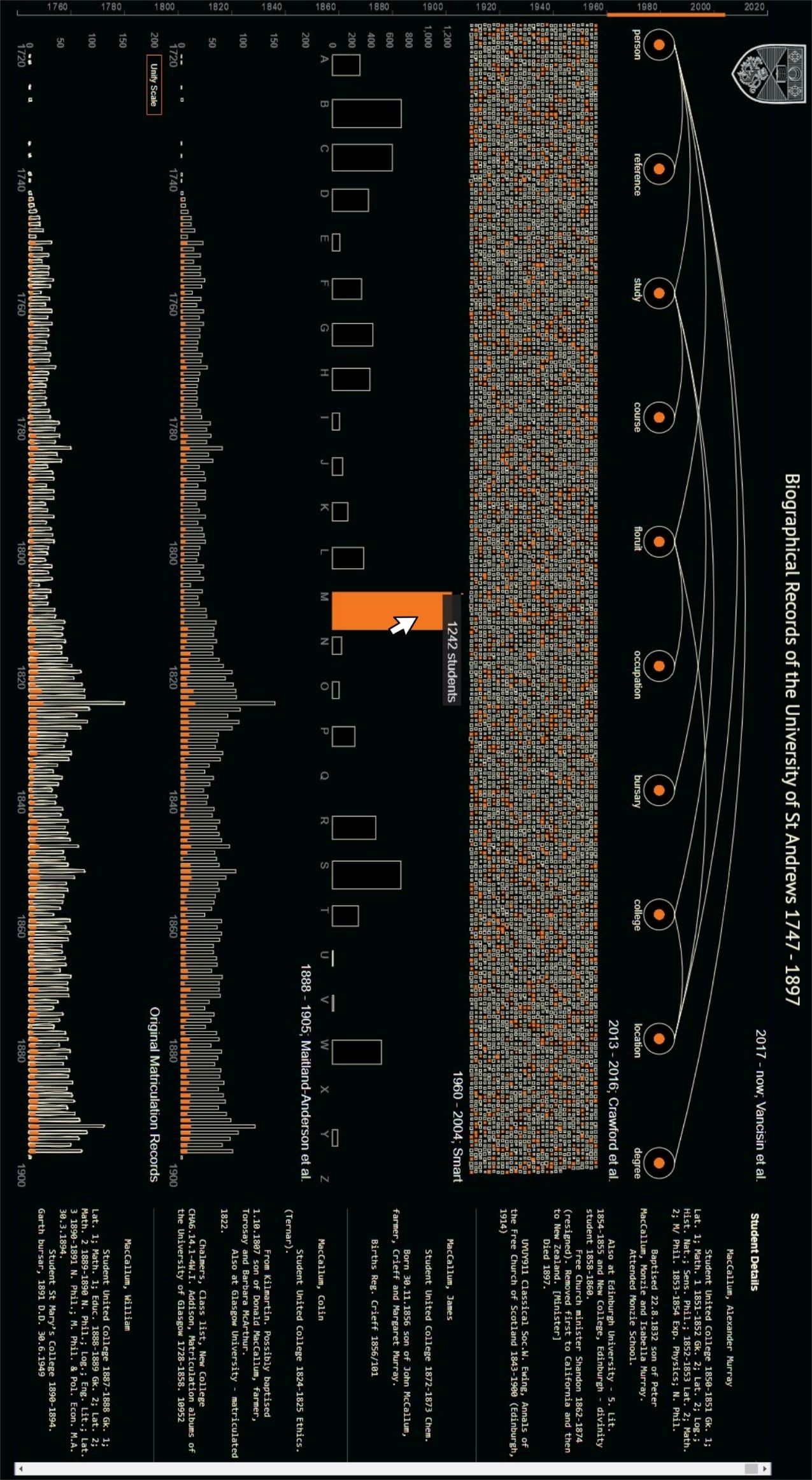

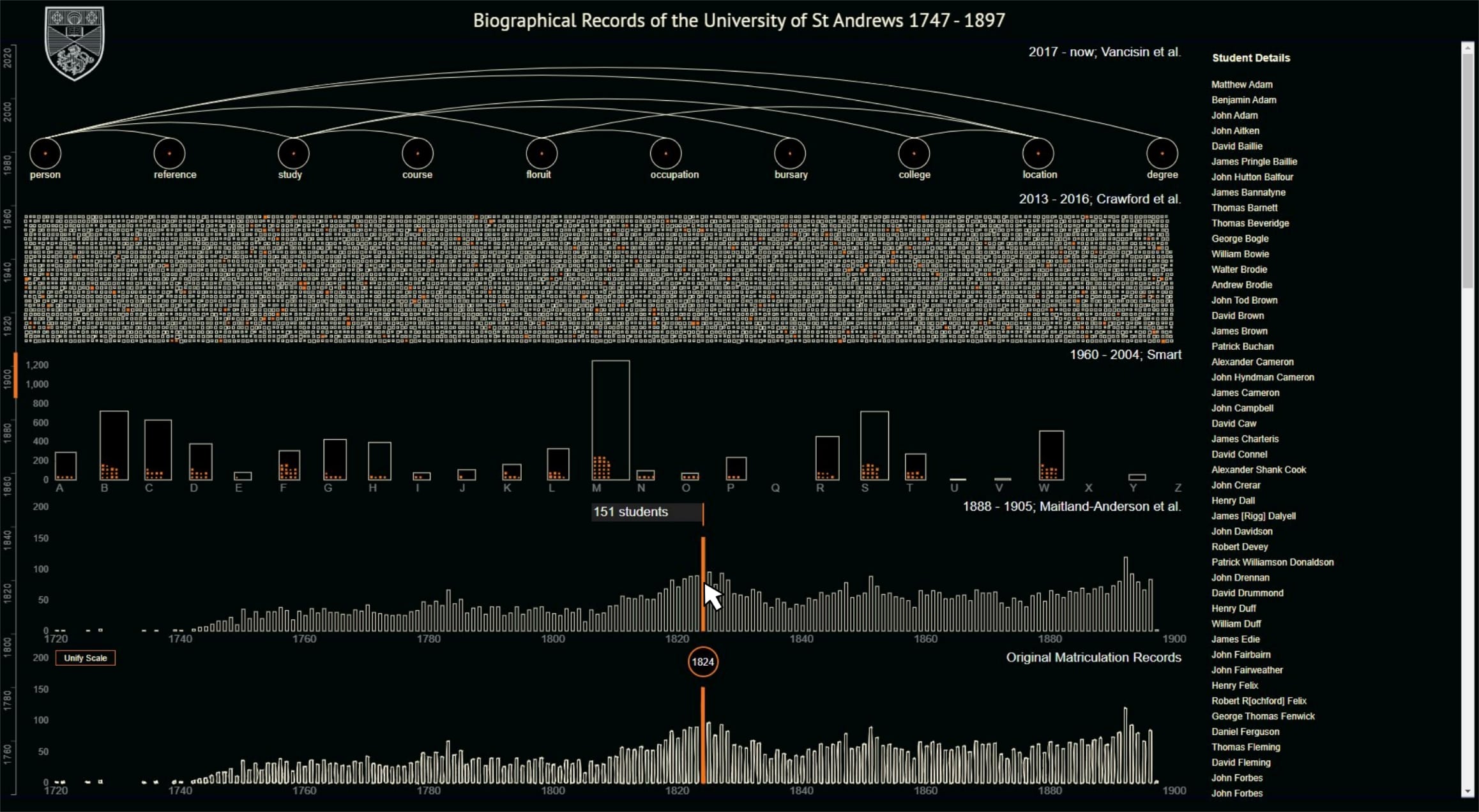

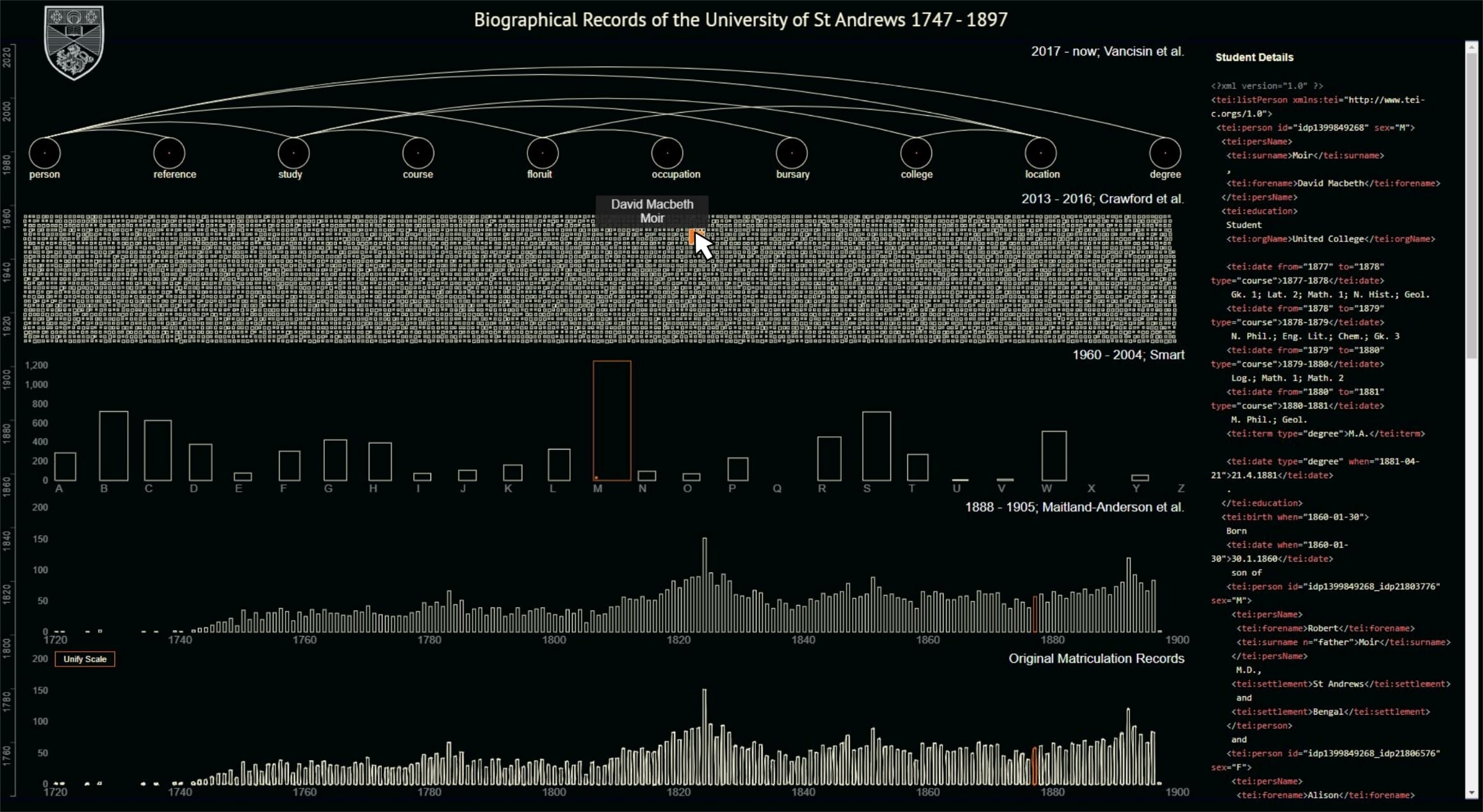

The bar chart at the bottom represents the temporal distribution of students in the original records (Fig. 3.1) while sketchy strokes emphasize the original records’ handwritten form. Subsequent transcriptions are depicted in an equivalent bar chart where smooth strokes show the records’ transformation into print (Fig. 3.2). The next layer highlights the records’ transformation into alphabetical order (reflecting Smart’s work) and the content expansion (represented by the bars’ width; Fig. 3.3). Crawford’s work revoked the records’ temporal or alphabetical ordering, so they are depicted as individual squares without any spatial organization (Fig. 3.4; square size corresponds to the amount of information in the record). Our database is shown in a horizontal node-link diagram where rectangles and arcs represent tables and their links (Fig. 3.5). All visualization layers are interactive and interlinked. Hovering over an element in one layer brings up the corresponding records in the record list view (Fig. 3.6) and highlights these in the other visualization layers (Fig. 4, 5 & 6).

Although based on the same data, this type of visualization fundamentally differs from previous approaches in that it enables an exploration of the student records through the lens of their historical context, and through the people involved in their curation and interpretation. Our work, thus, provides a new perspective on visualizing historical documents by illustrating how to allow for their exploration by also considering their history, rather than just their ‘final’ interpretation. Our visualization of qualitative curatorial changes has to be considered as yet another interpretation of the original records, but we see this approach as an opportunity to make transparent others’ and our own interpretations of such collections; it promotes awareness of both the dynamic and interpretative character of historical documents and their visualizations.

Our work combines the categorization of curatorial changes applied to the collection with their visualization, to promote transparency of the (re)-interpretations of the collection over time. Based on this case study, we launch discussion of design principles for visualizations that can make curatorial processes visible, in order to facilitate critical debate that centrally considers key curations of a collection over time (including pre-digital and early digitization), rather than rely only on ‘final’ data and/or final visualizations which often hide underlying interpretations that led to their assembly.

Figure 3: Process Visualization of BRUSA records. (1) Original Records, (2) Transcription, (3) Alphabetical index, (4) TEI files, (5) Database, (6) Student details. [Visualization available at https://tv8.host.cs.st-andrews.ac.uk/stAndrewsStudentBiorecords_contextVis].

Figure 3: Process Visualization of BRUSA records. (1) Original Records, (2) Transcription, (3) Alphabetical index, (4) TEI files, (5) Database, (6) Student details. [Visualization available at https://tv8.host.cs.st-andrews.ac.uk/stAndrewsStudentBiorecords_contextVis].

Figure 4: Interconnectedness of the records. Selecting the records starting with the letter "M" highlights these records in all the other visualization layers.

Figure 4: Interconnectedness of the records. Selecting the records starting with the letter "M" highlights these records in all the other visualization layers.

Figure 5: Interconnectedness of the records. Selecting the records from 1824 highlights these records in all the other visualization layers.

Figure 5: Interconnectedness of the records. Selecting the records from 1824 highlights these records in all the other visualization layers.

Figure 6: Interconnectedness of the records. Selecting the records from the TEI section highlights these records in all the other visualization layers.

Figure 6: Interconnectedness of the records. Selecting the records from the TEI section highlights these records in all the other visualization layers.

REFERENCES

Correll, M. (2019). Ethical Dimensions of Visualization Research. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’19, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300418

D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2016). Feminist data visualization. In Workshop on Visualization for the Digital Humanities (VIS4DH), Baltimore. IEEE.

Dörk, M., Feng, P., Collins, C., & Carpendale, S. (2013). Critical InfoVis: exploring the politics of visualization. In CHI'13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2189-2198). ACM.

Edelstein, D., Findlen, P., Ceserani, G., Winterer, C., & Coleman, N. (2017). Historical Research in a Digital Age: Reflections from the Mapping the Republic of Letters Project. American Historical Review (p. 25).

Forlini, S., Hinrichs, U., & Brosz, J. (2018). Mining the material archive: Balancing sensate experience and sense-making in digitized print collections. Open Library of Humanities.

Hinrichs, U., Alex, B., Clifford, J., Watson, A., Quigley, A., Klein, E., & Coates, C. M. (2015). Trading Consequences: ACase Study of Combining Text Mining and Visualiza-tion to Facilitate Document Exploration. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities (p. fqv046).

Hullman, J., & Diakopoulos, N. (2011). Visualization rhetoric: Framing effects in narrative visualization. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics, 17(12), 2231-2240.

Hyvönen, E., Leskinen, P., Heino, E., Tuominen, J., & Sirola, L. (2017) Reassembling and Enriching the Life Stories in Printed Biographical Registers: Norssi High School Alumni on the Semantic Web. In Language, Data, and Knowledge (Gracia, J., Bond, F., McCrae, J. P., Buitelaar, P., Chiarcos, C. & Hellmann, S. eds.) vol. 10318 pp.113–119. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Maitland Anderson, J. (1905). The Matriculation Roll of the University of St Andrews, 1747 – 1897. Edinburgh: Blackwood.

Péoux, G., & Houllier, J. R. (2017). To Visualize Past Communities: A Solution from Contemporary Practices in the Industry for the Digital Humanities. DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11(2).

Smart, R. N. (2004). Biographical Register of the University of St Andrews, 1747-1897. St Andrews University Library.

Vancisin, T., Crawford, A., Orr, M. M., & Hinrichs, U. (2018). From people to pixels: Visualizing Historical University Records. in Transimage 2018: Proceedings of the 5th Biennial Transdisciplinary Imaging Conference 2018. pp. 41-57, Transimage 2018, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 19/04/18. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6104699

Wrisley, D. (2018). Pre-visualization. IEEE 3rd Workshop for Visualization and the Digital Humanities.