1. Abstract

Modeling possible stories. A digital edition of Giovanni Domenico

Tiepolo's Divertimento per li Regazzi

Abstract

The paper presents a digital edition of Giovanii Domenico Tiepolo's drawing series Divertimento per li Regazzi. The series depict Pulcinella, a well-known character from the Commedia dell’Arte in different situations and can be interpreted as kind of a life story of the character. However, unlike in 'normal' narratives, the single drawings can not be ordered in one linear sequence but offer the recipient a variety of possibilities to arrange different stories. To model and visualize this open structure we draw on the CIDOC conceptual reference model and discuss a possible display for the front-end of the edition. Thus, the main contribution of the paper lies in the exploration of new ways for a digital presentation of narrative drawings series at the intersection of art history and narratology

Introduction

The drawing series Divertimento per li Regazzi created by the Venetian artist Giovanni

Domenico Tiepolo in the late 18th century lies at the intersection of narrative and figurative art: It features scenes that depict Pulcinella, the well-known character from the Commedia dell’Arte, in what appears to be different stages of his life, his birth, his adolescence or his death. Thus, the series can be ‘read’ as a kind of life story of Pulcinella. However, other than in linear narratives, the exact sequence of the drawings is unclear and even inconsistent. Furthermore, it is subverted by a playful arrangement of motifs that establish paradigmatic relationships between single drawings of the series or interlink them to works of other artists.

This richness of possible relations is hard to grasp with conventional means: In the printed catalogue by Adelheid Gealt[1], which still builds the base for scholarly research on the series, the drawings are – necessarily – presented in a static sequence that suggests a specific order of the pictures. As current endeavors in the field of textual scholarship have shown, such limitations of the printed media can be overcome with the help of digital editions that are able to present material in a dynamic way[2][3]. Thus, a transfer of these methods on figurative objects seems promising.

In our paper we want to report on our digital edition of the Divertimento, which takes into account the potential openness of the series and at the same time shows its

interconnectedness. For this purpose, we establish a data model that draws on the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model [4], which offers a solid, yet variable enough framework. Furthermore, we suggest a workflow that includes the conceptualization of a frontend that meets the requirements of a flexible display of the Divertimento. Therefore, the main contribution of our paper lies in the combination of different methods to establish new ways to present material at the intersection of textual and figurative art.

Divertimento per li Regazzi

The Divertimento consists of 104 drawings that depict Pulcinella in different situations. The individual Pulcinella-figures show enough resemblance to suggest that the series can be understood as a story of Pulcinella’s life from the cradle to the grave. However, because of numerous inconsistencies it is not possible to interconnect all the drawings into one concise narrative[5]. E.g., there are two drawings that show Pulcinella getting executed in two different ways and even one more drawing that shows his pardon. Thus, in contrast to ‘normal’ narratives, there is no clearly intended arrangement of a single plot. Instead, the series offers a wide range of possible stories, to be constructed by the recipient. Finding a way to handle these possibilities demands the application of specific perspectives that arrange the material in a manageable manner. E.g., from a narratological point of view, not all of the possible arrangements appear to be reasonable: Biographic readings of the series would suggest that drawings, which show Pulcinella as a child, should be sorted before pictures that show him as grown-up.

Furthermore, Pulcinella’s life story is supplemented by a paradigmatic dimension that is established by the repetition of specific motifs (e.g, several drawings contain a pot of gnocchi that suggests relations between those drawings). And finally, these internal

paradigmatic relations are supplemented by external links to other works of art, motifs or practices. The scene that depicts the shooting of Pulcinella, e.g., clearly refers to the Grandes Misères de la guerre of Jacques Callot, a contextualization, which sheds new light on the drawings.

This structure leads to several requirements for our edition:

- The goal of the edition should not be to reconstruct a single linear sequence, but rather to show possible links that are suggested by the series and enable the recipient to find diverse ways through the narrative space of the Divertimento.

- To achieve this goal, a data model is needed that provides a logical narrative framework without determining a fixed sequence.

- The data model has to take into account syntagmatic as well as paradigmatic relations.

- It should be capable to grasp internal as well as external references that reach out into the semantic web.

Workflow

To express the possible relations between the drawings we employ a graph data model by using RDF-triples and the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model. More concretely, we draw on the OWL-based version of the CIDOC, the Erlangen-CRM[6], which we adapted with the help of the ontology-editor Protégé[7]. The triples are stored in a graph database (GraphDB[8]).

We use the ARC2[9] framework to process SPARQL-queries in php and transform the results in HTML. To establish a link to Linked Open Data resources we use authority files like the iconclass classification system[10].

Modeling the data in CIDOC-CRM

A core concept of our approach is the modeling of our data in CIDOC-CRM, a top level ontology widely used in different contexts of the Digital Humanities [11]. We stick to the CIDOC-model not only for standardization purposes, but also because its event-centered structure is particularly apt for our goals. With the help of CIDOC, a flexible chronological structure can be established, which does not have to stick to a fixed sequence of single artefacts, but rather uses the notion of a ‘virtual’ life story to group the drawings of the Divertimento. Thus, the whole life story of Pulcinella (E4_Period) is segmented into subgroups of E5_Events (e.g., Pulcinella’s birth, childhood, or death) and E7_Activities (which further specify the events). E5_Events and E7_Activities are brought into a chronological order by using the relation P120_occurs_before.

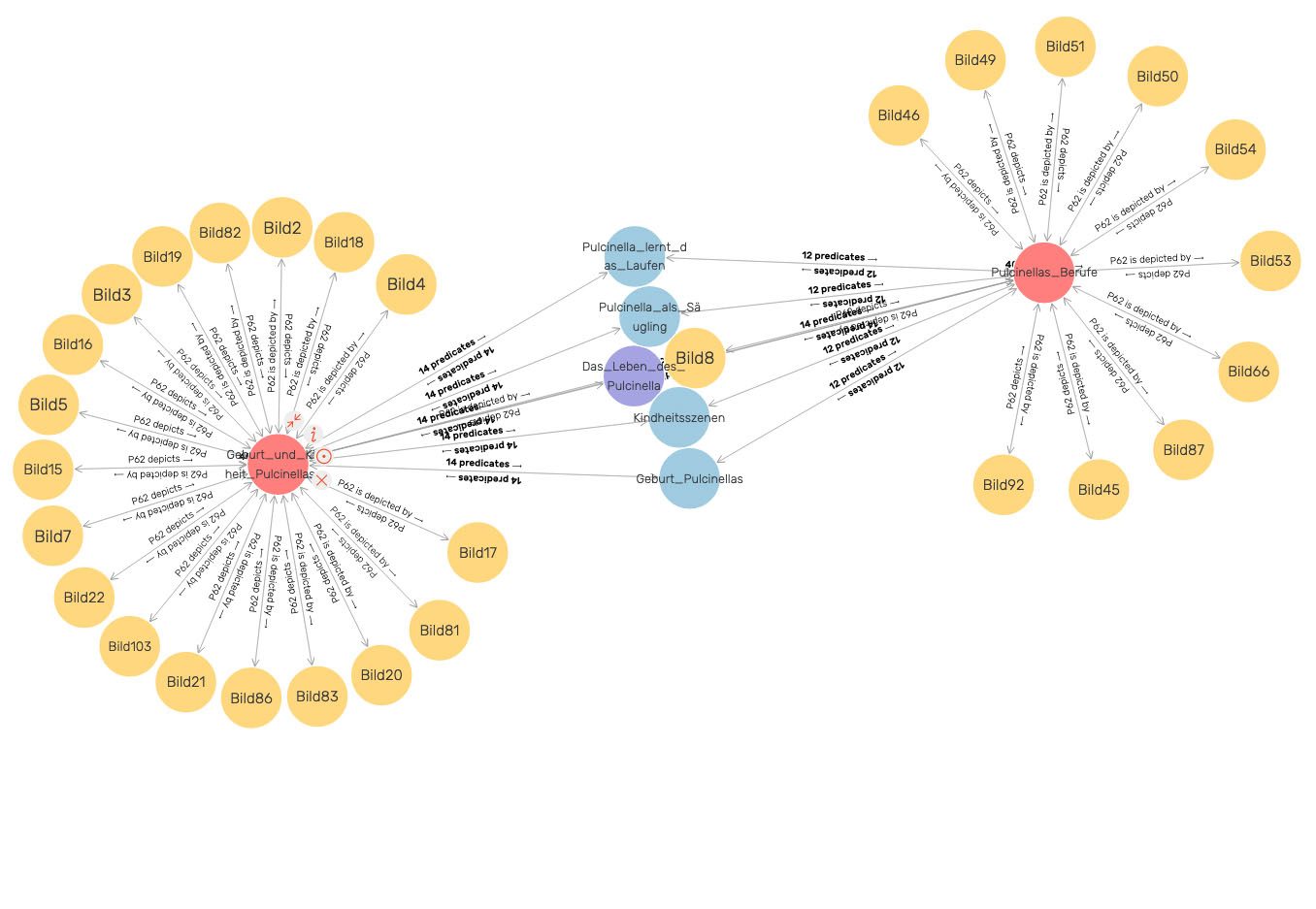

Figure 1 shows the two red E5_Event-nodes ‘Pulcinella’s birth and childhood’ and

‘Pulcinella’s professions’ and their connections. Yellow nodes represent the single drawings that are assigned to the E5_Events (note that some drawings like image 8, “the young Pulcinella observes the laborers”, can be assorted to two events). The two E5_Event-nodes are connected by various relations (amongst them P120_occurs_before) through E7_Activity-nodes (colored in light blue) that subdivide the events further. Both E5_Eventnodes are also connected to the overall E4_Period-node ‘Pulcinella’s life story’ in purple.

Figure 1: Detail from a network visualization of the data model, established with [8] (source: own)

Front end

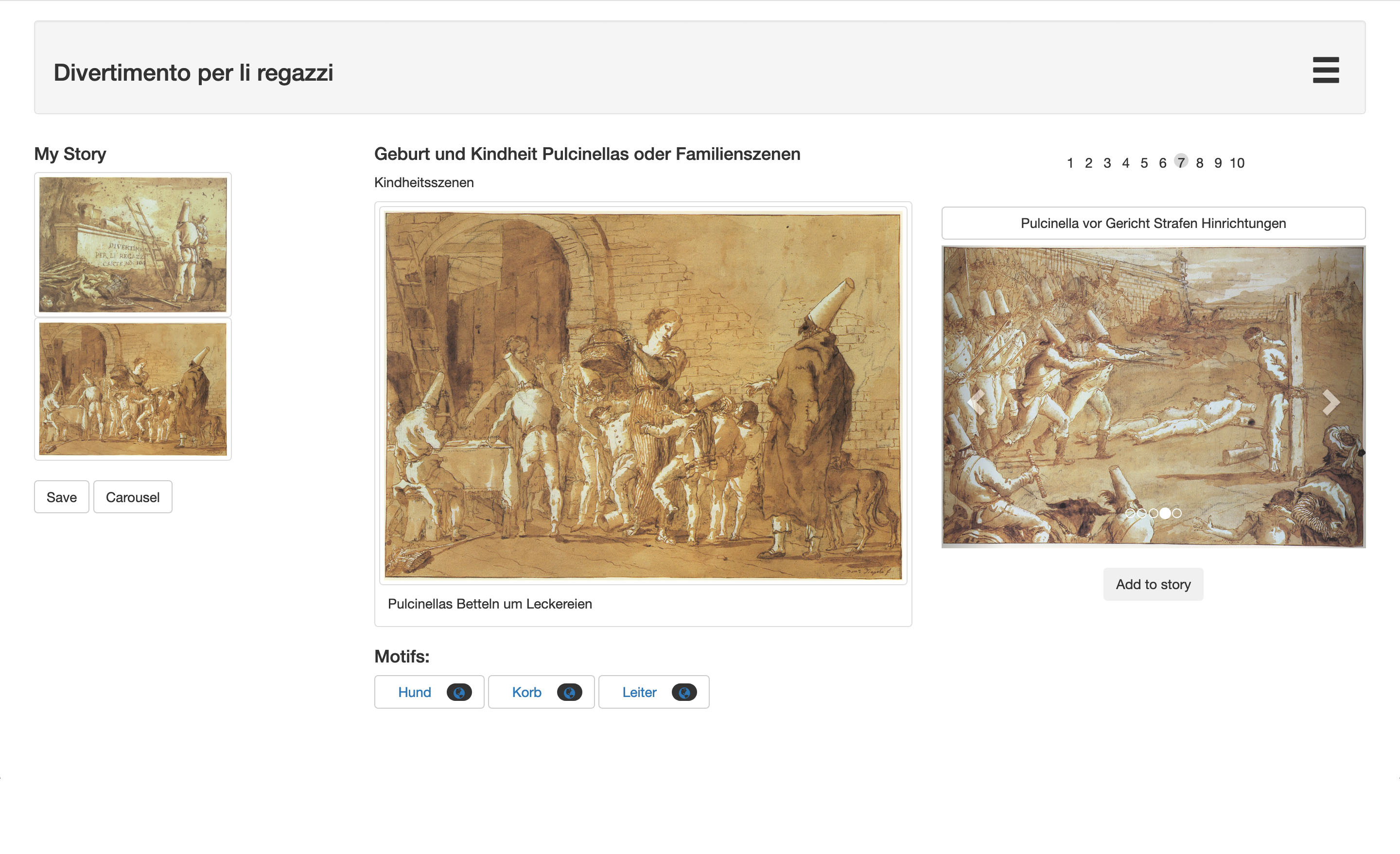

Figure 2 shows a prototype of the front end for the edition. It focuses on a single drawing in the middle and presents possible following events in a carousel in the right column, where the respective drawings can be selected to add up to an individual ‘story’. An overview of this story is presented in thumbnails in the left column.

The featured motifs of the drawing are listed beneath and can be selected to jump to

internal or external pictures that hold the same motifs, thus employing the paradigmatic relationships. Since all motifs are stored with their respective iconclass-ID, a further contextualization with resources of the semantic web can be achieved.

Figure 2: Prototype of the front end

References:

[1] Gealt, Adelheid M. (Ed.) (1986): Domenico Tiepolo. The Punchinello Drawings. New York: George Braziller.[2] Sahle, Patrick (2013): Digitale Editionsformen, Zum Umgang mit der Überlieferung unter den Bedingungen des Medienwandels. Norderstedt: Books on Demand.

[3] Pierazzo, Elena (2016): Modelling Digital Scholarly Editing: From Plato to Heraclitus, in: Driscoll, Matthew James and Pierazzo, Elena (eds.): Digital Scholarly Editing. Theories and Practices. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 41-58.

[4] Le Boeuf, Patrick / Doerr, Martin / Ore, Christian Emil / Stead, Stephen et al. (2019): “Definition of the CIDOCConceptual Reference Model”, Version 6.2.6 May 2019, http://www.cidoc-crm.org/sites/default/file/CIDOC%20CRM_v6.2.6_Definition_esIP.pdf

[5] Vetrocq, Marcia (1979): “Domenico Tiepolo and the Figure of Punchinello”, in: Gealt, Adelheid M. (eds..): Domenico Tiepolo’s Punchinello drawings. Bloomington: Indiana University Art Museum, 19-20.

[6] http://erlangen-crm.org/

[7] https://protege.stanford.edu/

[8] http://graphdb.ontotext.com/

[9] https://github.com/semsol/arc2

[10] http://www.iconclass.org/

[11] Eide, Øyvind / Ore, Christian-Emil Smith (2018): “Ontologies and data modeling”, in: Flanders, Julia / Jannidis, Fotis (eds): The Shape of Data in Digital Humanities. Modeling Texts and Text-based Resources. London: Routledge 178-196.