1. Abstract

Current techniques for typical NLP tasks such as plagiarism detection and paraphrase prediction do not necessarily work well for historical language text due to the heavy modification (caused by cul- tural and linguistic change, induction of errors, se- mantic change in meaning) that historical text is encountered with. To perform reuse (e.g., cita- tions, allusion) detection using machine or deep learning techniques, models are rare and text for a specific time period of genre exists seldom.

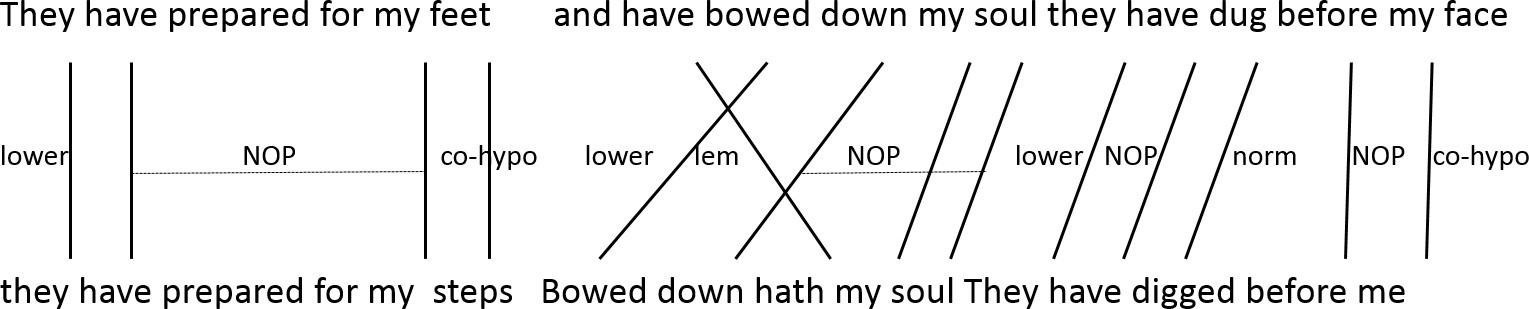

Previously, we modeled changes in parallel, his- torical English Bibles determining the ratio and type of modification. This work gives an under- standing of the degree, type and partition of mod- ification in historical text, which again is impor- tant to consider for example upfront a stylometry task. Modification can reach from inflection to replacement of semantically related words. Our approach therefore used normalizing tools and looked-up lexical databases (e.g., WordNet and BabelNet Navigli and Ponzetto (2010)) to identity semantic relations (synonymy, hyper(o)nymy, co- hyponymy, see Fig. 1). We found 90% of the rela- tions that two statistically aligned words share.

Now, we attempt to relate the last 10% using embedding representations of words from one pre- existing embedding model—based on historical English ranging from 1800 to 1900, henceforth StanHistEmb(1)—and one self-trained model— based on the Royal Society Corpus (Kermes et al., 2016)(2) ranging from 1665 to 1869, henceforth RoySocEmb). We think the latter performs bet- ter being tailored well to the actual historical vo- cabulary. We complete the work with first manual evaluation.

Before, Faruqui et al. (2015) refined word vec- tor representations using precise relations of semantic lexicons. Evaluation against shows a per- formance increase of 13% compared to earlier ap- proaches. Naya (2015) use neural models to pre- dict the correct hypernym of a word in a vec- tor space and achieves an accuracy of 20% for predicting whether the correct vector is among the 10 nearest. Weeds et al. (2014) train an SVM on word vector pairs achieving an error- rate-reduction of about 15% and find that distance scores between paired vectors work well for en- tailment tasks while adding vectors is useful for co-hyponymy determination.

Data Used: We use aligned Bibles from 1500–1900 (each with each other). Berkeley Aligner (Liang et al., 2006) aligns verse-aligned Bibles on token-level (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Modification examples during alignment

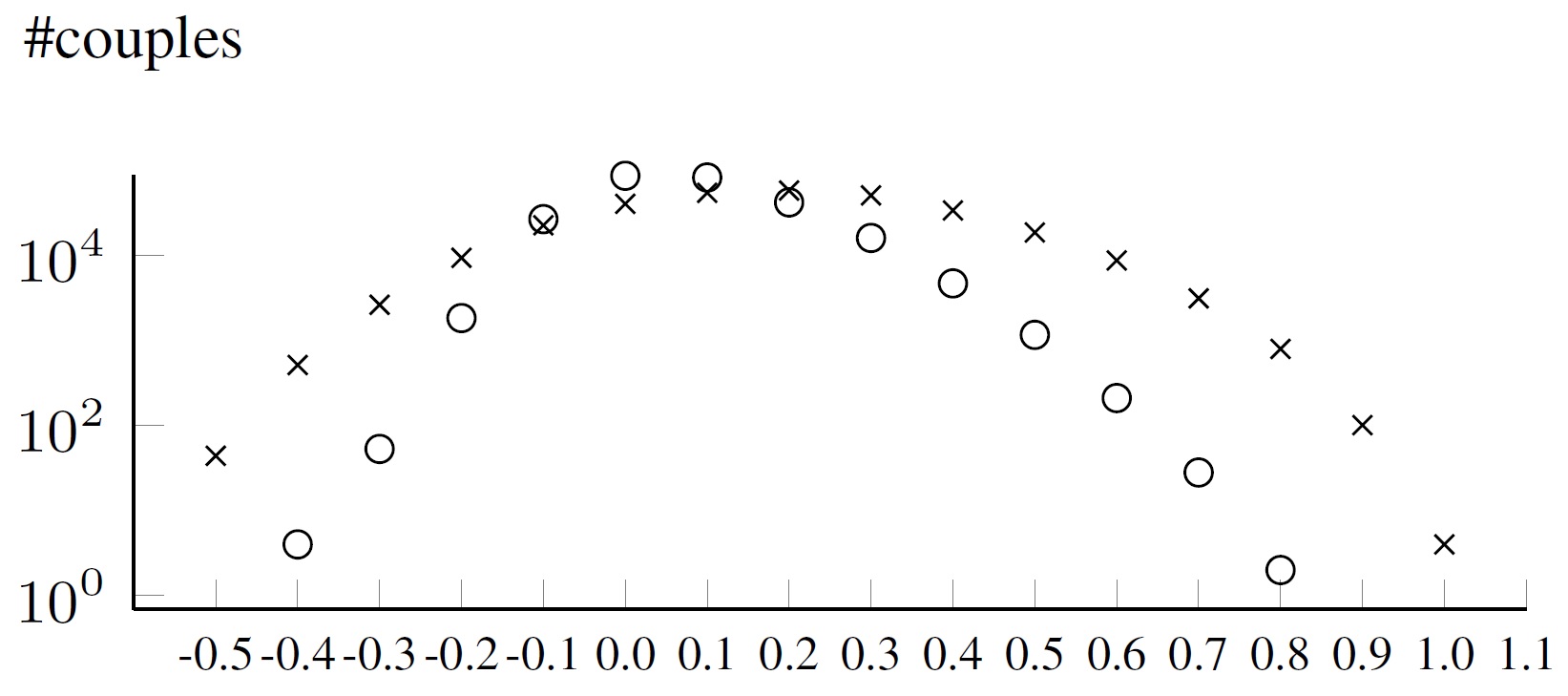

Recall Using StanHistEmb: First, we calcu- late the cosine distance for two word vectors us- ing the StanHistEmb vectors attempting to retrieve both words from each couple in the model. We find a cosine distance to 260,641 couples, which are normally distributed over the distance scale (see Figure 2, curve of o).(3)

Figure 2: Distribution of cosine distance measures of the word couples determined with the StanHistEmb (o) and the RoySocEmb (x) model

Recall Using RoySocEmb: Now, we calcu- late the cosine similarity for two words using a self-trained RoySocEmb model and the Gensim li- brary. We find a cosine score to 302,812, much more than using StanHistEmb. Here, couples are even better normally distributed (Figure 2, curve of x), but values are lower due to a better tailored model, which in the sum is much smaller while supporting more historical vocabulary.(4)

Precision Using StanHistEmb: We manually evaluate 138 sample couples that have a cosine similarity(5) > .5. We assign 1.0 when two words are synonyms and 0.0 when there is no semantic relation(6) (see Table 1). Principally, scores from 0.0 to 0.4 represent false positives. While many couples scored above .5 are strongly related or synonym. We not yet manually evaluated sam- ples for RoySocEmb. However, we looked up the same samples using that model and find 119 out of which 69 scored > .5 and 77 scored > .4. How- ever, looking at the skipped couples, they tend to be false positives for high similarity.(7)

manual score no. of couples example

0.0 0 -

0.1 1 thyself,wilt

0.2 3 hast,thine

0.3 0 -

0.4 0 -

0.5 1 firebrands,darts

0.6 2 forgive,pray

0.7 27 wife,daughter

0.8 70 openly,publicly

0.9 34 hip,thigh

1.0 0 -

Table 1: Semantic relation score between word cou- ples filtered using a cosine similarity of > .5 using the StanHistEmb model

Forecast: We plan to investigate the selftrained model of Early Modern English more deeply. Specially to see in more detail whether and how the size of the model influences the accu- racy of the words’ relations. Therefore, we con- sider to refine the pre-trained model by retrain- ing and consider joining both models, because the RoySocEmb fits our time, but not our domain.(8)

References

Manaal Faruqui, Jesse Dodge, Sujay Kumar Jauhar, Chris Dyer, Eduard Hovy, and Noah A Smith. 2015. Retrofitting word vectors to semantic lexicons. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computa- tional Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pages 1606–1615.

Hannah Kermes, Stefania Degaetano-Ortlieb, Ashraf Khamis, Jörg Knappen, and Elke Teich. 2016. The royal society corpus: From uncharted data to corpus. In LREC.

Percy Liang, Ben Taskar, and Dan Klein. 2006. Align- ment by agreement. In Proceedings of the Human Language Technology Conference of the NAACL, Main Conference, pages 104–111. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Roberto Navigli and Simone Paolo Ponzetto. 2010. Babelnet: Building a very large multilingual seman- tic network. In Proceedings of the 48th annual meet- ing of the association for computational linguistics, pages 216–225. Association for Computational Lin- guistics.

Neha Naya. 2015. Learning hypernymy over word em- beddings. In Deep Learning for Natural Language Processing - Project Reports. Stanford University.

Julie Weeds, Daoud Clarke, Jeremy Reffin, David Weir, and Bill Keller. 2014. Learning to distinguish hyper- nyms and co-hyponyms. In Proceedings of COL- ING 2014, the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers, pages 2249–2259. Dublin City University and Association for Computational Linguistics.

1) https://nlp.stanford.edu/projects/histwords/

2) Containing text from articles, reviews and abstracts

3) 351,169 contain out-of-vocab words; 64,305 are as- signed “nan” through by-zero-division

4) 373,303 couples were not retrieved using RoySocEmb.

5) We normalize the distance score.

6) Evaluation is done by a German native with proficient knowledge in English.

7) We consider to fold the scores in future experiments down to a scale of only three or four digits. For now, we follow the value range between zero and one.

8) In accordance with the RSC, we plan to publish our embedding models.