1. Abstract

Novel World-Building: Science Fiction

Introduction

This project explores two narrative techniques that allow authors of Science Fiction (SF) to create and communicate invented worlds.

Explicit Worldbuilding: Microgeneric worldbuilding

Explicit worldbuilding--moments that appear to merely convey worldbuilding information--is simultaneously widely acknowledged as a unifying feature of the genre1 yet derided as “witless, even infantile.”2 Questions of when and how much explicit worldbuilding happens, then, might help us answer questions about prestige and more fundamental questions about the form of SF.

After initial feature-finding forays into explicit worldbuilding, we turned to the Lit Lab’s Microgenres project,3 hoping to replicate their work on a specifically SF corpus. The Microgenres project seeks to identify extra-disciplinary discourses within narrative using a non-lexical approach. We hypothesized that moments of explicit worldbuilding might resemble these disciplinary discourses.

Corpus

To test this hypothesis, we assembled a test corpus of 17 SF novels and 26 science texts written by Isaac Asimov, sampled to comparable size.

Methods

With the Microgenres feature set (including frequency of Penn Treebank POS tags, average sentence length, average number of clauses per sentence, and numbers of named entity persons), we created a classification model using linear discriminant analysis. By training a model on 20- and 50-sentence subsections of our corpus of science writing and then classifying similarly-sized passages of SF, we can use the posterior probabilities of the classification results to identify the mixture of science writing in each part of each SF novel.

Analysis

This section of the project seeks to answer two related questions. First, are there significant stylistic differences in Asimov’s science and science fiction? And, second, if those stylistic differences exist, can we identify moments where science style appears in SF?

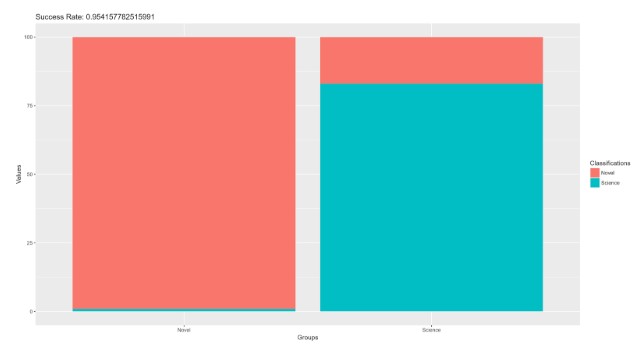

To answer the first question: yes. Our classification model had a success rate of 95% at the 50-sentence level and 91% at the 20-sentence level (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Classification success rate, 50-sentence slices

Figure 1: Classification success rate, 50-sentence slices

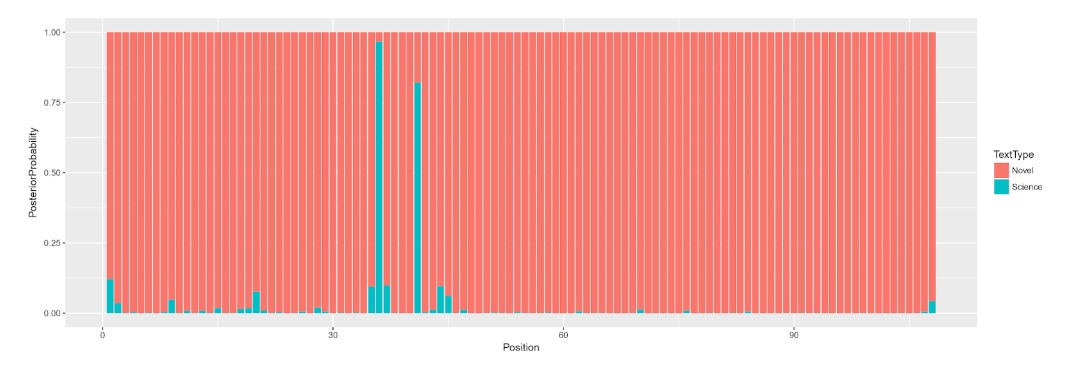

To answer the second question, we classified slices in each of the novels. For example, in the resulting graph of Second Foundation (Figure 2), each bar represents a 50-sentence slice of the text and the distribution of colors indicates the posterior probabilities of each discourse in each slice as assigned by the model. Slice 36, with the most “science,” contains an essay on the history of the Foundation.

Figure 2: Classification of 50-sentence slices of Second Foundation

Figure 2: Classification of 50-sentence slices of Second Foundation

(Im)probabilities and Worldbuilding

In implicit worldbuilding, authors juxtapose tokens that are familiar to readers within contexts in which their co-occurrence is unexpected, such as“the door dilated.”4 While both “door” and “dilated” are familiar to readers, their unexpected co-occurrence signals a new world.

Corpus

To explore the role of syntagmatic pairs in implicit worldbuilding we expanded our corpus to include 246 SF novels published between 1905 and 2017, which we compared to a combined corpus of 146 novels from the same period tagged as “realism” and a corpus of 311,580 journal articles from Scientific American and the Journal of the British Medical Association (JBMA).5

Methods

We tested normalized pointwise mutual information (NPMI) as a means to identify such bigrams as above, but the sensitivity of PMI to low frequency words (rather than low frequency word pairings) made it unable to detect bigrams of the kind we sought. Our interest, in this particular project, is in improbable or novel combinations of otherwise normal frequency words--and the signal of those improbably-combined words are drowned out by the noise created by pairings of low-frequency words.

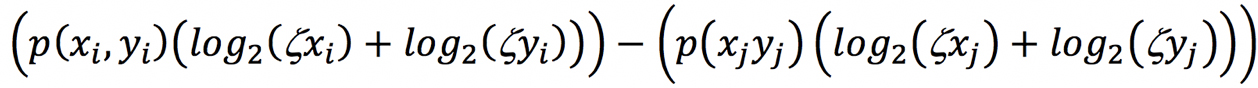

In order to identify implicit worldbuilding, we introduce a new metric, improbability, as a way of measuring the significance of word pairs whose constituent elements occur in reference corpora, but whose combination is relatively unique to our target corpus.

Subtraction of the probability of words x and y following each other in our reference corpus from our target corpus gave too much significance to instances in which rare tokens in the non-SF corpus skewed the probability of their co-occurrence. Accordingly, we scaled the resulting metric using the zeta measure of significance for the terms.6 This adjusted our metric to account for the relative significance of the terms in our corpora as described in Figure 3.7

Results

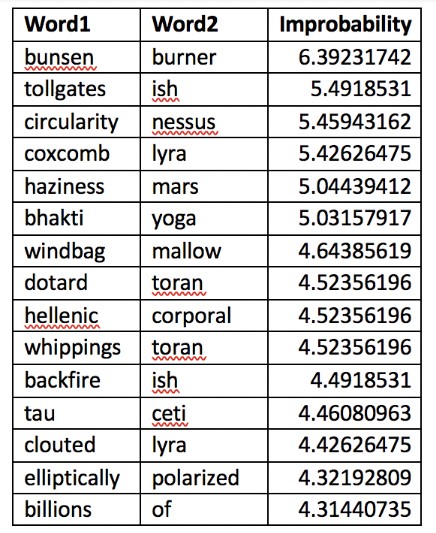

The 15 most improbable word combinations indicative of SF when compared to the realism and JStor corpus are shown in Table 1. Our metric captures both syntagmatic worldbuilding (“haziness mars”) and a semiotics of science which places familiar objects in unfamiliar narrative contexts (“bunsen burner”).

Table 1: Most improbable bigram sequences in SF novels

Table 1: Most improbable bigram sequences in SF novels

We are also able to calculate the improbability score of all bigrams in a given segment of text. This allows us to locate segments of novels with a large number of improbable word combinations, not only revealing passages of specific novels in which implicit worldbuilding occurs, but laying the groundwork for uncovering larger patterns across novels.

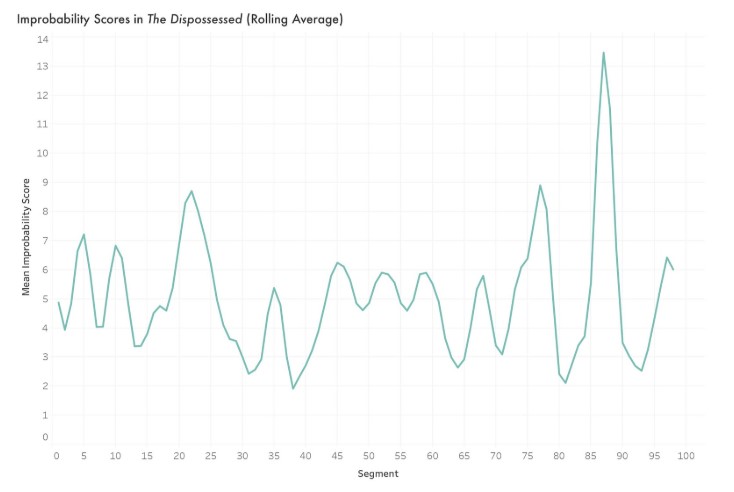

Figure 4: Improbability scores across The Dispossessed

Figure 4: Improbability scores across The Dispossessed

For example, Figure 4 shows a smoothed plot of the improbability scores across Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. We divided the novel into 100 overlapping segments, calculated the improbability score in each, and averaged the results across windows of 3 adjacent segments, revealing two peaks. Our metric captured these important moments of worldbuilding, both of which depict the narrator struggling to make sense of his situation.

Conclusions

The two methods we employ, microgenres and improbility, have proven successful at identifying key moments of worldbuilding in SF. More importantly, the two metrics correspond to explicit and implicit worldbuilding, creating the opportunity to study not just individual examples of how these two strategies are employed by authors at the level of the text, but also patterns that differentiate SF from other literary genres.

Endnotes:

1Russ, “Towards an Aesthetics of Science Fiction.” (1975)

2 Angenot, “The Absent Paradigm: An Introduction to the Semiotics of Science Fiction.” (1979)

3 Algee-Hewitt, Mark, Michaela Bronstein, Abigail Droge, Erik Fredner, Eva Grant, Ryan Heuser, Xander Manshel, Nichole Nomura, J.D. Porter, and Kelsey Reardon. (2019). “Microgenres: A Computational Model of Disciplinarity and the Novel.” Presentation, Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations Conference, Utrecht.

4 Ellison, Harlan. “A Voice from the Styx,” (1968)

5 JStor Data For Research (https://www.jstor.org/dfr/). Accessed: October, 2018

6 Schöch, Christof, Daniel Schlör, Albin Zehe, Henning Gebhard, Martin Becker, Andreas Hotho. “Burrows’ Zeta: Exploring and Evaluating Variants and Parameters” Digital Humanities 2018 (July, 2018)

Evert, Stefan, Fotis Jannidis, Thomas Proisl, Steffen Pielström, Thorsten Vitt, Christof Schöch, and Isabella Reger. (2017) “Understanding and Explaining Distance Measures for Authorship Attribution.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities (https://academic.oup.com/dsh/article-pdf/32/suppl_2/ii4/21298943/fqx023.pdf)

Burrows, John. (2006). “All the way through: Testing for Authorship in Different Frequency Strata.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 22(1): 27-47.

7 We follow Schöch et al., 2018 in using a log transformation of our zeta scores to increase their significance.